Viral hepatitis

| Viral hepatitis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Micrograph showing ground glass hepatocytes, which are seen in chronic hepatitis B infections (a type of viral hepatitis), and represent accumulations of viral antigen in the endoplasmic reticulum. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | None, fever, tiredness, abdominal pain, vomiting, dark urine, yellowish skin[1] |

| Complications | Cirrhosis, liver failure, liver cancer[2] |

| Duration | Short or long-term[2] |

| Causes | Hepatitis A, B, C, D, E, X[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests[3] |

| Prevention | Vaccination, sanitation[1][4] |

| Treatment | Supportive, medications, liver transplant[1] |

| Frequency | Short-term: >10 million[5][6] Long-term: 325 million[7] |

Viral hepatitis is liver inflammation (hepatitis) due to a viral infection.[2] It may present as a short-term (acute) or long-term (chronic) infection.[2][1] Symptoms may vary from none, to fever, tiredness, abdominal pain, vomiting, dark urine, and yellowish skin.[1] The long-term form can result in cirrhosis, liver failure, or liver cancer.[2]

Most commonly it occurs due to five unrelated viruses hepatitis A, B, C, D, or E.[2] Hepatitis A and E typically spread through food and water that have been contaminated with stool.[2] Hepatitis B, C, and D are typically spread through contact with infected blood.[2] Cases were the cause is not clear may be called non-A–E hepatitis or hepatitis X.[2] A number of other viruses, such as herpes simplex, have been implicated.[8] Diagnosis is by blood tests.[3]

Hepatitis A and B can be prevented by vaccination, while hepatitis A and E can be prevented by improvements in sanitation.[1][4] Hepatitis A and E will often resolve on their own.[2][1] Effective treatments for long-term hepatitis C are available but costly.[9][10] Medications may also be used for long-term hepatitis B.[11] Liver transplant may be required to address complications.[1]

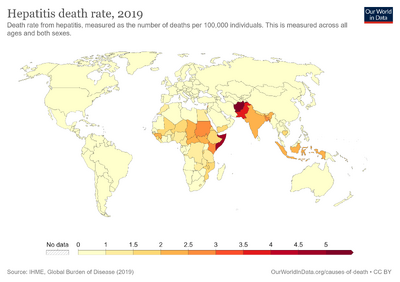

Long-term viral hepatitis affects about 325 million people globally (257 million with hepatitis B and 71 million with hepatitis C).[7][4] Outbreaks of hepatitis A and E occur worldwide, affecting at least 10 million people a year, mostly in developing countries.[4][5][6] It is the most common cause of liver inflammation.[1] In 2013, about 1.5 million people died from viral hepatitis, most commonly due to hepatitis B and C.[12] East Asia and South Asia are the most commonly affected regions.[12] Infectious hepatitis was first determined in the 1940s.[5]

Types

The most common cause of hepatitis is viral,[13] although the effects of various viruses are all classified under the disease hepatitis, these viruses are not all related as seen below in chart.

| Hepatitis A (HAV)[14][15][16] | Hepatitis B (HBV)[17][18][19] | Hepatitis C (HCV)[20][21] | Hepatitis D (HDV)[22][23] | Hepatitis E (HEV)[24][25] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral species | Hepatovirus A | Hepatitis B virus | Hepacivirus C | Hepatitis delta virus | Orthohepevirus A |

| Viral family | Picornaviridae | Hepadnaviridae | Flaviviridae | Incertae sedis | Hepeviridae |

| Genome | (+)ssRNA | dsDNA-RT | (+)ssRNA | (−)ssRNA | (+)ssRNA |

| Antigens | HBsAg, HBeAg | Core antigen | Delta antigen | ||

| Transmission | Enteral | Parenteral | Parenteral | Parenteral | Enteral |

| Incubation period | 20–40 days | 45–160 days | 15–150 days | 30–60 days | 15–60 days |

| Severity/Chronicity | Mild; acute | Occasionally severe; 5–10% chronic | Subclinical; 70% chronic | Exacerbates symptoms of HBV; chronic with HBV | Mild in normal patients; severe in pregnant women; acute |

| Vaccine | 10 year protection | 3 injections, lifetime protection | None available | None available | Investigational (approved in China) |

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A or infectious jaundice is caused by hepatitis A virus (HAV), a picornavirus transmitted by the fecal-oral route often associated with ingestion of contaminated food. It causes an acute form of hepatitis and does not have a chronic stage. The patient's immune system makes antibodies against HAV that confer immunity against future infection. People with hepatitis A are advised to rest, stay hydrated and avoid alcohol. A vaccine is available that will prevent HAV infection for up to 10 years. Hepatitis A can be spread through personal contact, consumption of raw sea food, or drinking contaminated water. This occurs primarily in third world countries. Strict personal hygiene and the avoidance of raw and unpeeled foods can help prevent an infection. Infected people excrete HAV with their feces two weeks before and one week after the appearance of jaundice. The time between the infection and the start of the illness averages 28 days (ranging from 15 to 50 days),[26] and most recover fully within 2 months, although approximately 15% of sufferers may experience continuous or relapsing symptoms from six months to a year following initial diagnosis.[27]

| Marker | Detection Time | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faecal HAV | 2–4 weeks or 28 days | – | Early detection |

| Ig M anti HAV | 4–12 weeks | Enzyme immunoassay for antibodies | During acute Illness |

| Ig G anti HAV | 5 weeks–persistent | Enzyme immunoassay for antibodies | Old infection or reinfection |

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is caused by the hepatitis B virus, a hepadnavirus that can cause both acute and chronic hepatitis. Chronic hepatitis develops in the 15% of adults who are unable to eliminate the virus after an initial infection. Identified methods of transmission include contact with blood, blood transfusion , sex (through sexual intercourse or contact with bodily fluids), or mother-to-child by breast feeding;[11][19] there is minimal evidence of transplacental crossing. Blood contact can occur by sharing syringes in intravenous drug use, shaving accessories such as razor blades, or touching wounds on infected persons, hence needle-exchange programmes have been created in many countries as a form of prevention.[29][30]

Individuals with chronic hepatitis B have antibodies against the virus, but not enough to clear the infected liver cells. The continued production of virus and countervailing antibodies is a likely cause of the immune complex disease seen in these patients. A vaccine is available to prevent infection for life, Hepatitis B infections result in two billion people having been infected worldwide of which 360 million have chronic infection. Hepatitis B is endemic in a number of countries, making cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma big killers.[19][31][32]

There are eight treatment options approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) available for persons with a chronic hepatitis B infection: alpha-interferon, pegylated interferon, adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, lamivudine, tenofovir disoproxil and tenofovir alafenamide with a 65% rate of sustained response.[11][19][33]

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C (originally "non-A non-B hepatitis") is caused by hepatitis C virus (HCV), an RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae. HCV can be transmitted through contact with blood (including through sexual contact if the two parties' blood is mixed) and can also cross the placenta. Hepatitis C usually leads to chronic hepatitis, culminating in cirrhosis in some people. It usually remains asymptomatic for decades. Patients with hepatitis C are susceptible to severe hepatitis if they contract either hepatitis A or B, so all persons with hepatitis C should be immunized against hepatitis A and hepatitis B if they are not already immune, and avoid alcohol. HCV can lead to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, however, only a minority of HCV-infected individuals develop cancer (1-4% annually), suggesting a complex interplay between viral gene expression and host and environmental factors to promote carcinogenesis. The risk is increased two-fold with active HBV coinfection and a 21% increase in mortality compared to those with latent HBV and HCV.[34][35] HCV viral levels can be reduced to undetectable levels by a combination of interferon and the antiviral drug ribavirin. The genotype of the virus is the primary determinant of the rate of response to this treatment regimen, with genotype 1 being the most resistant.[36]

Hepatitis C is the most common chronic blood-borne infection in the United States.[37]

| Marker | Detection Time | Description | Significance | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV-RNA | 1–3 weeks or 21 days | PCR | Demonstrates presence or absence of virus | Results may be intermittent during course of infection. Negative result is not indicative of absence. |

| anti-HCV | 5–6 weeks | Enzyme Immunoassay for antibodies | Demonstrates past or present infection | High false positive in those with autoimmune disorders and populations with low virus prevalence. |

| ALT | 5–6 weeks | – | Peak in ALT coincides with peak in anti-HCV | Fluctuating ALT levels is an indication of active liver disease. |

Liver cancer

Hepatitis C causes acute and chronic infections that is a major cause of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).[39]

A major cause of death in HCC patients with chronic HCV infection. The pathogenesis of HCC associated with HCV, that virus play direct and indirect roles.[40]A major risk for the development of HCC is persistent infection with HCV and the highest risk for HCC development is associated with co-infection of HBV with HDV, HCV or HIV.[41]

The risk factors lead to development of HCC in chronic HCV is synchronous liver diseases, viral genotype, lifestyle factors and presence of obesity and diabetes mellitus. The lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol use and coffee drinking accelerated progression to HCC in HCV.[42][43]

The purpose of HCV treatment is to eliminate the infection, reduce the transmission to other people and decrease the risk of HCC development.[39]

Hepatitis D

Hepatitis D is caused by the hepatitis D virus (HDV), or hepatitis delta virus; it belongs to the genus Deltavirus. It is similar to a viroid as it can only propagate in the presence of the hepatitis B virus, depending on the helper function of HBV for its replication and expression. It has no independent life cycle, but can survive and replicate as long as HBV infection persists in the host body. It can only cause infection when encapsulated by hepatitis B virus surface antigens.[23][44][45]

Hepatitis E

Hepatitis E is caused by the Hepatitis E virus (HEV), from the family Hepeviridae; it produces symptoms similar to hepatitis A, although it can take a fulminant course in some patients, particularly pregnant women; chronic infections may occur in immune-compromised patients. It is more prevalent in the Indian subcontinent. The virus is feco-orally transmitted and usually is self-limited.[25][46]

Hepatitis F

Hepatitis F virus (HFV) is a hypothetical virus linked to certain cases of hepatitis. Several hepatitis F virus candidates emerged in the 1990s, but none of these reports have been substantiated.[47][48]

GB virus C

The GB virus C is another potential viral cause of hepatitis that is probably spread by blood and sexual contact.[49] It was initially identified as Hepatitis G virus.[50] There is very little evidence that this virus causes hepatitis, as it does not appear to replicate primarily in the liver.[51] It is now classified as GB virus C.[52]

Other viruses

The virus first known to cause hepatitis was possibly the yellow fever virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus.[53] Other viruses than can cause hepatitis include:

- Adenoviruses[54]

- Arenaviruses: Guanarito virus, Junín virus, Lassa fever virus, Lujo virus, Machupo virus, and Sabiá virus[55]

- Rift Valley fever virus[56]

- Coronavirus: severe acute respiratory syndrome virus[57]

- Erythrovirus: Parvovirus B19[58]

- Flaviviruses: dengue, Kyasanur Forest disease virus, Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus, and yellow fever virus [59]

- Herpesviruses: cytomegalovirus,[60]Epstein–Barr virus,[61] varicella-zoster virus,[62] human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 7, and human herpesvirus 8[63]

- Orthomyxoviruses: influenza[64]

- Reovirus: Reovirus 3 (may cause)[65]

KIs-V is a virus isolated in 2011 from four patients with raised serum alanine transferases without other known cause; a causal role is suspected.[66]

Epidemiology

Over 30,000 cases of hepatitis A were reported to the CDC in the US in 1997, but the number has since dropped to less than 2,000 cases reported per year.[67]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 "Hepatitis". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 "What Is Viral Hepatitis?". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. NIDDK. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Hepatitis Testing". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Global Viral Hepatitis: Millions of People are Affected | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 10 February 2021. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Viral hepatitis : acute hepatitis. Cham, Switzerland. 2019. ISBN 978-3-030-03534-1. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "WHO-recommended surveillance standard of acute viral hepatitis". WHO. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Hepatitis". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ Kaufman, B; Gandhi, SA; Louie, E; Rizzi, R; Illei, P (March 1997). "Herpes simplex virus hepatitis: case report and review". Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 24 (3): 334–8. doi:10.1093/clinids/24.3.334. PMID 9114181.

- ↑ "Hepatitis C". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. NIDDK. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ "What is Viral Hepatitis?". www.cdc.gov. CDC. 17 February 2021. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Hepatitis B | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Stanaway, Jeffrey D; Flaxman, Abraham D; Naghavi, Mohsen; Fitzmaurice, Christina; Vos, Theo; Abubakar, Ibrahim; Abu-Raddad, Laith J; Assadi, Reza; Bhala, Neeraj; Cowie, Benjamin; Forouzanfour, Mohammad H; Groeger, Justina; Hanafiah, Khayriyyah Mohd; Jacobsen, Kathryn H; James, Spencer L; MacLachlan, Jennifer; Malekzadeh, Reza; Martin, Natasha K; Mokdad, Ali A; Mokdad, Ali H; Murray, Christopher J L; Plass, Dietrich; Rana, Saleem; Rein, David B; Richardus, Jan Hendrik; Sanabria, Juan; Saylan, Mete; Shahraz, Saeid; So, Samuel; Vlassov, Vasiliy V; Weiderpass, Elisabete; Wiersma, Steven T; Younis, Mustafa; Yu, Chuanhua; El Sayed Zaki, Maysaa; Cooke, Graham S (July 2016). "The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". The Lancet. 388 (10049): 1081–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30579-7. PMC 5100695. PMID 27394647.

- ↑ Mehta, Parth; Reddivari, Anil Kumar Reddy (2022). "Hepatitis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 10 January 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ↑ "Hepatitis A Vaccination: For Healthcare Providers | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 5 May 2022. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ↑ Melnick, J. L. (1992). "Properties and classification of hepatitis A virus". Vaccine. 10 Suppl 1: S24–26. doi:10.1016/0264-410x(92)90536-s. ISSN 0264-410X. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (22 December 2021). "Hepatitis A Virus (HAV)". FDA. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ "Hepatitis B Vaccination: For Providers | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 5 May 2022. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ↑ Schaefer, Stephan (7 January 2007). "Hepatitis B virus taxonomy and hepatitis B virus genotypes". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (1): 14–21. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i1.14. ISSN 1007-9327. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Tripathi, Nishant; Mousa, Omar Y. (2022). "Hepatitis B". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ "Flaviviridae: Hepacivirus C Classification | ICTV". ictv.global. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ Basit, Hajira; Tyagi, Isha; Koirala, Janak (2022). "Hepatitis C". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ↑ Magnius, Lars; Taylor, John; Mason, William S.; Sureau, Camille; Dény, Paul; Norder, Helene. "ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Deltavirus". Journal of General Virology. 99 (12): 1565–1566. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.001150. ISSN 1465-2099. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Masood, Umair; John, Savio (2022). "Hepatitis D". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ Meng, Xiang-Jin (1 January 2021). "Hepeviruses (Hepeviridae)". Encyclopedia of Virology (Fourth Edition). Academic Press. pp. 397–403. ISBN 978-0-12-814516-6. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Waqar, Sana; Sharma, Bashar; Koirala, Janak (2022). "Hepatitis E". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ "CDC Hepatitis A FAQ". Archived from the original on 1999-05-05. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ↑ "CDC Hepatitis A Fact Sheet". Archived from the original on 1998-12-05. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ↑ "Acute Viral Hepatitis : Introduction Harrison's Principle of Internal Medicine, 17 Edition". Archived from the original on 2001-07-26. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- ↑ "Syringe Services Programs (SSPs) FAQs | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 7 December 2020. Archived from the original on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ↑ "Hepatitis infection among people who use or Inject drugs | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 22 April 2021. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ↑ Trépo, Christian; Chan, Henry L. Y.; Lok, Anna (6 December 2014). "Hepatitis B virus infection". Lancet (London, England). 384 (9959): 2053–2063. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60220-8. ISSN 1474-547X. Archived from the original on 7 December 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ↑ Shepard, C. W. (1 June 2006). "Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Epidemiology and Vaccination". Epidemiologic Reviews. 28 (1): 112–125. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxj009. Archived from the original on 16 December 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ↑ De Clercq, Erik (November 2015). "Current treatment of hepatitis B virus infections". Reviews in Medical Virology. 25 (6): 354–365. doi:10.1002/rmv.1849. ISSN 1099-1654. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ↑ Ringehan, Marc; McKeating, Jane A.; Protzer, Ulrike (2017-10-19). "Viral hepatitis and liver cancer". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 372 (1732): 20160274. doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0274. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 5597741. PMID 28893941.

- ↑ "Hepatitis C and Dietary Supplements". NCCIH. Archived from the original on 7 January 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ Pianko, S.; McHutchison, J. G. (June 2000). "Treatment of hepatitis C with interferon and ribavirin". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 15 (6): 581–586. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02082.x. ISSN 0815-9319. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ↑ "CDC DVH—Hepatitis C Information For the Health Professional". Archived from the original on 2009-11-25. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- ↑ "WHO | Hepatitis C". Who.int. 2010-12-08. Archived from the original on 2004-10-02. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Axley, Page; Ahmed, Zunirah; Ravi, Sujan; Singal, Ashwani K. (28 March 2018). "Hepatitis C Virus and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Narrative Review". Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology. 6 (2): 1–6. doi:10.14218/JCTH.2017.00067. Archived from the original on 16 October 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ de Oliveria Andrade, Luis Jesuino; D'Oliveira, Argemiro; Melo, Rosangela Carvalho; De Souza, Emmanuel Conrado; Costa Silva, Carolina Alves; Paraná, Raymundo (2009). "Association Between Hepatitis C and Hepatocellular Carcinoma". Journal of Global Infectious Diseases. 1 (1): 33–37. doi:10.4103/0974-777X.52979. ISSN 0974-777X. PMC 2840947. PMID 20300384.

- ↑ Ringehan, Marc; McKeating, Jane A.; Protzer, Ulrike (2017-10-19). "Viral hepatitis and liver cancer". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 372 (1732). doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0274. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 5597741. PMID 28893941.

- ↑ Zhang, Xinhe; Guan, Lin; Tian, Haoyu; Zeng, Zilu; Chen, Jiayu; Huang, Die; Sun, Ji; Guo, Jiaqi; Cui, Huipeng; Li, Yiling (9 September 2021). "Risk Factors and Prevention of Viral Hepatitis-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma". Frontiers in Oncology. 11: 686962. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.686962. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ↑ Kuper, H; Tzonou, A; Kaklamani, E; Hsieh, CC; Lagiou, P; Adami, HO; Trichopoulos, D; Stuver, SO (15 February 2000). "Tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption and their interaction in the causation of hepatocellular carcinoma". International journal of cancer. 85 (4): 498–502. PMID 10699921. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ↑ "Hepatitis D | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ↑ "What is Hepatitis D - FAQ | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 3 December 2020. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ↑ Zeng, Dan-Yi; Li, Jing-Mao; Lin, Su; Dong, Xuan; You, Jia; Xing, Qing-Qing; Ren, Yan-Dan; Chen, Wei-Ming; Cai, Yan-Yan; Fang, Kuangnan; Hong, Mei-Zhu; Zhu, Yueyong; Pan, Jin-Shui (1 September 2021). "Global burden of acute viral hepatitis and its association with socioeconomic development status, 1990–2019". Journal of Hepatology. 75 (3): 547–556. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2021.04.035. ISSN 0168-8278. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ↑ Fagan, E. A.; Harrison, T. J. (16 December 2003). Viral Hepatitis. Garland Science. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-135-32643-2. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ Kiyosawa, K.; Tanaka, E. (1995). "[Hepatitis F virus]". Ryoikibetsu Shokogun Shirizu (7): 20–23. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ Stark K, Bienzle U, Hess G, Engel AM, Hegenscheid B, Schluter V (1996). "Detection of the hepatitis G virus genome among injecting drug users, homosexual and bisexual men, and blood donors". J. Infect. Dis. 174 (6): 1320–3. doi:10.1093/infdis/174.6.1320. PMID 8940225.

- ↑ Linnen J, Wages J, Zhang-Keck ZY, et al. (1996). "Molecular cloning and disease association of hepatitis G virus: a transfusion-transmissible agent". Science. 271 (5248): 505–8. Bibcode:1996Sci...271..505L. doi:10.1126/science.271.5248.505. PMID 8560265.

- ↑ Pessoa MG, Terrault NA, Detmer J, et al. (1998). "Quantitation of hepatitis G and C viruses in the liver: evidence that hepatitis G virus is not hepatotropic". Hepatology. 27 (3): 877–80. doi:10.1002/hep.510270335. PMID 9500722.

- ↑ "00.026. Flaviviridae". ICTVdB Index of Viruses. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

- ↑ Fonseca, José Carlos Ferraz da (2010). "[History of viral hepatitis]". Revista Da Sociedade Brasileira De Medicina Tropical. 43 (3): 322–330. doi:10.1590/s0037-86822010000300022. ISSN 1678-9849. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ↑ Schaberg, Kurt B.; Kambham, Neeraja; Sibley, Richard K.; Higgins, John P. T. (June 2017). "Adenovirus Hepatitis: Clinicopathologic Analysis of 12 Consecutive Cases From a Single Institution". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 41 (6): 810–819. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000834. ISSN 1532-0979. Archived from the original on 2023-01-16. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ↑ Miguet JP, Coaquette A, Bresson-Hadni S, Lab M (1990). "[The other types of viral hepatitis]". Rev Prat (in français). 40 (18): 1656–9. PMID 2164704.

- ↑ Shope, Robert E. (1996). "Bunyaviruses". Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. Archived from the original on 2022-08-10. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ↑ Chau TN, Lee KC, Yao H, et al. (February 2004). "SARS-associated viral hepatitis caused by a novel coronavirus: report of three cases". Hepatology. 39 (2): 302–10. doi:10.1002/hep.20111. PMC 7165792. PMID 14767982.

- ↑ Naides SJ (May 1998). "Rheumatic manifestations of parvovirus B19 infection". Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 24 (2): 375–401. doi:10.1016/S0889-857X(05)70014-4. PMID 9606764.

- ↑ Pierson, Theodore C.; Diamond, Michael S. (June 2020). "The continued threat of emerging flaviviruses". Nature Microbiology. 5 (6): 796–812. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0714-0. ISSN 2058-5276. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ↑ Xiong W (November 2010). "[Clinical efficacy of treating infant cytomegalovirus hepatitis with ganciclovir and impact on cytokines]". Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi (in 中文). 26 (11): 1130–2. PMID 21322282.

- ↑ Okano M, Gross TG; Gross (November 2011). "Acute or Chronic Life-Threatening Diseases Associated With Epstein-Barr Virus Infection". Am. J. Med. Sci. 343 (6): 483–9. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318236e02d. PMID 22104426. S2CID 38640928.

- ↑ Anderson, D.R.; Schwartz, J.; Hunter, N.J.; Cottrill, C.; Bissaccia, E.; Klainer, A.S. (1994). "Varicella Hepatitis: A Fatal Case in a Previously Healthy, Immunocompetent Adult". Archives of Internal Medicine. 154 (18): 2101–2106. doi:10.1001/archinte.1994.00420180111013. PMID 8092915.

- ↑ Gallegos-Orozco JF, Rakela-Brödner J; Rakela-Brödner (October 2010). "Hepatitis viruses: not always what it seems to be". Rev Med Chil. 138 (10): 1302–11. doi:10.4067/S0034-98872010001100016. PMID 21279280.

- ↑ Papic N, Pangercic A, Vargovic M, Barsic B, Vince A, Kuzman I (September 2011). "Liver involvement during influenza infection: perspective on the 2009 influenza pandemic". Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 6 (3): e2–5. doi:10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00287.x. PMC 4941665. PMID 21951624.

- ↑ Becker, Yechiel; Huang, E.-S.; Darai, Gholamreza (6 December 2012). Molecular Aspects of Human Cytomegalovirus Diseases. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 73. ISBN 978-3-642-84850-6. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ↑ Satoh K, Iwata-Takakura A, Osada N, et al. (October 2011). "Novel DNA sequence isolated from blood donors with high transaminase levels". Hepatol. Res. 41 (10): 971–81. doi:10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00848.x. PMID 21718400.

- ↑ "Hepatitis A Information for Health Professionals — Statistics and Surveillance". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

External links

| Classification |

|---|