Troika (1969 film)

| Troika | |

|---|---|

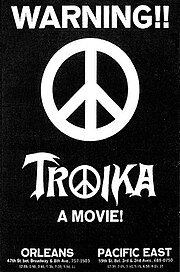

1969 promotional poster | |

| Directed by | Fredric Hobbs Gordon Mueller |

| Written by | Fredric Hobbs |

| Produced by | Fredric Hobbs |

| Starring | Fredric Hobbs Richard Faun Morgan Upton Nate Thurmond Gloria Rossi Parra O'Siochain |

| Cinematography | William Heick[1] |

| Edited by | Gordon Mueller |

| Music by | Fredric Hobbs Gordon Mueller |

Production company | Inca Films |

| Distributed by | Emerson Film Enterprises[2] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 89 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Troika is a 1969 American comedy anthology-art film written, directed, and produced by artist-turned-filmmaker Carl Fredric Hobbs. It stars Hobbs, Richard Faun, Morgan Upton, Nate Thurmond, Gloria Rossi, and members of the San Francisco Art Institute. Its three parts are built around a fictional account of the director's attempt to gain financing for a film titled "Troika".

Hobbs conceived the outline after working with the filmmakers Ron Bostwick and Robert Blaisdell on the short film Trojan Horse. Inspired, he began to develop a "modern morality play", with a title borrowed from the Russian word for a set of three, embodied by the three overlapping segments. The film was shot in early to mid-1969, in various locations in and around California. The score was composed in a collaborative effort between Hobbs and the editor-co-director Gordon Mueller.

Troika was previewed on October 12, 1969, before officially premiering that year on November 8. It received little attention from film critics, with reviews being mixed to positive. Yet the film became foundational for Hobbs' career and led to his three other films, before he retired from the industry in the late 1970s. The film is largely unavailable to the general public, and has yet to receive a home media release. Hobbs blocked Troika releases on home video as he was unhappy with the final print. In 2022, a copy restored by Glasgow's Centre for Contemporary Arts in collaboration with Hobbs' estate was screened at the Weird Weekend Cult Film Festival.

Plot

Troika' abandons conventional narrative structure, being composed of an introductory story and three parts, each told in differing narrative styles. Although the three sections are not titled in the film, in interviews Hobbs has named them as "The Chef", "Alma Mater" and "The Blue People".[3][4]

The film opens with an artist–Fredric Hobbs portraying a fictional version of himself– paints upon a blank canvas. The scene then transistions to a series of encounters between Hobbs and the Hollywood producer Gordon Goodloins (Richard Faun) as the former attempts to convince him to invest in a proposed art film titled Troika. Goodloins relents and agrees to hear out Hobbs' proposal. Later, the two men meet and discuss the cinematic connections between art and life concerning his vision for the film. Goodloins is unimpressed by the idea and rebuffs him, suggesting that there is no consumer demand for art films. The sequence ends with Goodloins driving off in a limousine as Hobbs angrily chases behind him, shouting, "Up yours, Mr. Goodloins!"

The Chef

In this segment, a chef wearing ritualistic face paint, begins crafting an alchemical and culinary brew inside a large vat, into which he throws items such as medals and emblems. Nearby, a homunculus (an artificial human) fashioned out of cloth lies inert as the chef uses pieces of it as ingredients for the concoction. Unsatisfied with the results, the chef introduces a woman, played by Gloria Rossi, covered in painted symbols. They dance before he throws her into the pot. Picking up a rose she had dropped, the chef gazes at it before also tossing it into the vat.

Alma Mater

Presented in documentary style, the second segment depicts a student demonstration in the late 1960s. It opens during a sit-in on a college campus as mounted police gather outside. In the classroom, students covered in white face paint rest on toilet seats and chaise longues while college professors lecture students. After six professors complete their lectures, the frustrated students boo a dunce-capped teacher out of the classroom.

The Blue People

The final segment opens with a train stopping in a grassy landscape. Exiting the train is a tall insectoid named Rax (Morgan Upton), who travels into the nearby coastal hills. Rax is later attacked on the road by a feral human (Parra O'Siochain), who leaves him for dead. The injured Rax staggers onto a beach, where he collapses and convulses in pain as an orange-colored woman (Rossi) emerges from the ocean, pushing a large sculpture. Seeing the injured Rax, the woman turns her attention to him, caressing his wounds and eventually masturbating in front of him.

The shot abruptly cuts to a seemingly rejuvenated Rax entering an ice-covered cave where he encounters a seven-foot-tall shaman known as the Attenuated Man (Nate Thurmond). Addressing Rax in distorted Arabic, he induces a vision of a sculpture depicting three corpse-like beings emerging from the cave's ceiling. Dispersed throughout the segment are clips of a procession of the blue people proceeding across an otherworldly countryside, accompanied by a strange vehicle. At this point, the segment cuts from the cave as Rax, alongside the Attenuated Man, joins the blue people who embrace him as their "savior". The procession escorts Rax in regal splendor as it marches through a ghost town, sparsely populated by blue and purple people, before they arrive at a railway terminal. There Rax bids the group goodbye as he boards the train, and the sequence ends with a shot of Rax as he merges with the sculpture of the three beings.

The film then cuts back to Hobbs as he has completed the painting, unveiled as a grotesque figure of a woman whose extended arm hangs the faces and forms of humanity. Satisfied with the painting, Hobbs exists the frame and the film ends.

Production

Development

Hobbs studied for a career as an artist, graduating from Cornell University in 1953 with a bachelors degree in arts.[5][6] Between the late 1950s and early 1960s, he produced a series of acclaimed paintings and sculptures known for their unique and often avant-garde style,[7] which explored environmentalist and spiritualist themes. In 1967, Hobbs collaborated with the filmmakers Ron Bostwick and Robert Blaisdell on a twenty-five minute[Note 1] short documentary on his 'parade sculpture' Trojan Horse, a metal sculpture bolted over a Chrysler chassis cab.[10][11] During the collaboration, Hobbs became fascinated with film as an art form and began to develop the concept for Troika, which he described as a "modern miracle play – but not underground".[8][12] The film was financed by Hobbs and the independent production company Inca Films.[12][13]

Troika was developed during the arthouse cinematic movement in the late 1960s,[14] where the narrative is told through an entirely visual exploration of ideas opposite to a clear story-driven narration.[14] The film expands upon Hobbs' prior works, exploring environmental and spiritual themes through visual narration.[8] The dialogue of the Attenuated Man, according to Hobbs, was taken from a portion of the Quran discussing the concept of Universal Brotherhood then manipulated and distorted later in post production.[15] While contemporary writers categorized the film as a comedy or art film,[16][17] it incorporates several different narratives and genres for each segment.[8] Hobbs crafted Troika as a series of increasingly bizarre segments, with the final segment being his favorite.[8] For the "Alma Mater" segment, shot in the narrative style of an expressionist documentary film, Hobbs reportedly took his inspiration from the Kent State riots,[4] which occurred in 1967 and later in April 1969.[18]

Hobbs mainly cast unknown performers, several of whom have no other acting credits. Hobbs appears as a fictionalized version of himself and as the chef and fantom characters.[19] The San Francisco-based basketball player Nate Thurmond plays the mystical Attenuated Man in the final segment;[3][4] one writer described the character as a Christ-like figure.[20] Morgan Upton, later known for his roles as Wally Henderson in The Candidate (1972)[21] and Mr. Gilfond in Peggy Sue Got Married (1986),[22] appears as Rax, the bug-man.[3][4] Members of the San Francisco Art Institute were hired for several other roles, including the blue and purple people, and the students in the "Alma Mater" scene.[23][3] Some of the characters in the marching sequence were student activists from the UC Berkeley School of Law.[4]: 359

Filming

Principal photography began in 1969. Gordon Mueller was hired as the editor and directed scenes where Hobbs was on camera.[4] The photographer and filmmaker William Heick was hired as cinematographer he was a close friend of Hobbs and had worked separately with the filmmakers Sidney Peterson and Robert Gardner between 1948 and 1953.[8][24] The "Chef" sequence was shot inside a local brewery, where the crew utilized the brewer's vat as a stand-in for the chef's alchemy pot.[4]: 358

For the "Alma Mater" sequence, Hobbs utilized the faculty at the San Francisco Art Institute, with, according to the San Francisco Examiner, additional filming taking place in Hillsborough, California.[25] The documentary footage in the segment was shot during the 1960s Berkeley protests.[16] Scenes of the ghost town in the final "Blue People" sequence were filmed in Collinsville, California, while the "otherworldly" landscape was shot in the outskirts of a town where a brush fire had recently occurred. Hobbs extensively drilled the student activists portraying the characters during the marching sequence to march in step.[4]: 359 Hobbs intended to include a sequence involving Thurmond's character as he runs alongside the skyline. The scene was filmed at Fort Cronkhite, but was abandoned when the military fired Nike missiles during an artillery exercise, ruining the shot.[26]

Hobbs designed all the costumes, and many of the background paintings and sculptures were taken from his earlier artworks. He produced the soundtrack with the co-director Mueller, generating sounds that Thrower described as echoing the works of the avant-garde composer La Monte Young.[4]: 359

Release

Troika received its first preview screening on October 12, 1969.[20] The artworks and sculptures created for the film were exhibited at the John Bolles Gallery in San Francisco on November 8 of that year,[25] and the film had its official premiere in New York on November 21.[23] It was screened at the Granada Theater in Wilmington, California on November 28, as a double feature alongside John Perry's short film Dandelion (1969).[27][28] During its release, some theaters ran advertisements with the caption "Means Three",[29] a translation of the Russian name the title was based on.[30] Troika aired on UK and Canadian television between May and December 1979.[31][32][33]

Hobbs repeatedly blocked its release on home video as he was dissatisfied with the print and was holding off until he finished an edit he ultimately had not completed by the time of his death in 2018.[8] The only known print of the film, which included additional materials is stored at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archives.[34][35][36]

Prints were unobtainable to the general public until October 2022 when the Centre for Contemporary Arts in Glasgow, in collaboration with Hobbs' estate, acquired a copy for restoration efforts by the American Genre Film Archive.[37][36] The film was screened for the first time in over fifty years at the Weird Weekend Cult Film Festival on October 28, 2022.[38] As of 2024 there have been no further announcements or screenings.

Reception

Reviews of Troika have been largely positive, with critics praising its unique visual style and narrative. In 1969, Howard Thompson of The New York Times highlighted the unconventional plot, describing the film as "a cluttered and disconnected collage of art objects, paintings, live-action fantasy and symbolism".[17] Its surreal and psychedelic visuals were also praised by video retail company Blockbuster Video, in their annual movie guide, described as a "wildly offbeat look at the movie business".[39] The TV Guide echoed this sentiment while also noting that the film would only appeal to viewers who did not mind its unconventional narrative.[40]

While the film's cinematography and narrative were generally well-received, they were criticized by some writers. Cue magazine described the cinematography as "grotesque", lambasting it as a self-indulgent parade of sequences "devoid of talent".[41] Kevin Thomas of The Los Angeles Times wrote that the narrative was original but incoherent while the comedic elements were too heavy-handed to be funny.[16] The LA Times dismissed it "obscure and boring".[42] In a 1969 review, Wanda Hale of the Daily News wrote that while the film had artistic merit, it was compromised by "amateurish" production.[3]

Legacy

After the release of Troika, Hobbs developed three additional films in the 1970s.[6][11] In 1970, Hobbs was approached by pornographic film producer Habib Afif Carouba who offered to fund the director's next film, with the stipulation that it would be an adult film.[12][43] The resulting Roseland: A Fable (1970), is a surreal philosophical satire on the porn industry. The film gained controversy due to its sexual content, which was considered scandalous for a mainstream film at the time.[44]

In 1973 Hobbs increased his theatrical output, writing and directing what would be his final two films.[45] The first was Alabama's Ghost (1973), a horror film that combines the themes and motifs of blaxploitation and vampire films.[46] His final film, Godmonster of Indian Flats (1973), continued his exploration of the blaxploitation genre, placing the film in a horror western setting.[11] Both were critical and commercial failures,[45][47] which, combined with behind-the-scenes conflicts with producers caused Hobbs to grow discontent with the film industry, who later retired from filmmaking.[45]

References

Notes

- ^ While some sources list the runtime as thirty minutes,[5][8] a 1968 publication from the Library of Congress gives the runtime as twenty-five minutes.[9]

Citations

- ^ Nash & Ross 1985, p. 1290.

- ^ Aros 1977, p. 461.

- ^ a b c d e Hale 1969, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Thrower 2007, pp. 357–359.

- ^ a b Albright 1985, p. 107.

- ^ a b Thrower 2007, p. 363.

- ^ Frankenstein 1965, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f g Thrower 2007, p. 364.

- ^ Library of Congress 1968, p. 487.

- ^ The Art Gallery 1967, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Hinckle & Hobbs 1978, p. 173.

- ^ a b c Albright, Thomas (April 29, 1971). "Visuals: Two films from San Francisco artist Frederic Hobbs". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Jimenez, Laird (July 3, 2018). "Fredric Hobbs And The Cult Afterlife Of GODMONSTER OF INDIAN FLATS". Birth.Movies.Death. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Bordwell 1979, pp. 56–64.

- ^ Thrower 2007, p. 360.

- ^ a b c Thomas 1969a, p. 106.

- ^ a b Thompson 1969.

- ^ Means 2016, pp. 22–26.

- ^ Lee 1972, p. 504.

- ^ a b Lewis 1969, p. 88.

- ^ Aros 1977, p. 64.

- ^ Welsh, Phillips & Hill 2010, p. 267.

- ^ a b "Troika". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Aitken 2013, p. 282.

- ^ a b Morch 1969, p. 51.

- ^ Lynch 1971, p. 8.

- ^ Los Angeles Free Press 1969, p. 6.

- ^ The Los Angeles Times 1969, p. 26.

- ^ Los Angeles Evening Citizen 1969, p. 8.

- ^ Thrower 2007, p. 357.

- ^ Red Deer Advocate 1979, p. 50.

- ^ Birmingham Post 1979, p. 1.

- ^ Edmonton Journal 1979, p. 90.

- ^ "Troika". Berkley.edu. University of California Berkeley. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ "Fredric Hobbs motion pictures--outtakes. Selects". Berkley.edu. University of California Berkeley. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Troika (Fredric Hobbs, 1969)". Weird Weekend Cult Film Festival. October 12, 2022. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ Matchbox Cine (October 12, 2022). "Matchbox Cine on Twitter". Twitter. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ "WEIRD WEEKEND III: Troika". Center for Contemporary Arts. October 28, 2022. Archived from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ Castell 1995, p. 1159.

- ^ "Troika - Movie Reviews and Movie Ratings". TV Guide. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ Glankoff 1969, p. 3.

- ^ Thomas 1969b, p. 28.

- ^ Weldon 1996, p. 474.

- ^ Bladen 1971, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Thrower 2007, p. 371.

- ^ Renshaw, Jerry (January 1, 1999). "Scanlines: Alabama's Ghost". The Austin Chronicle. Vol. 18, no. 18. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ Renshaw, Jerry (October 17, 1997). "Scanlines: The Godmonster of Indian Flats". The Austin Chronicle. Vol. 17, no. 7. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

Sources

Books

- Library of Congress Catalog: Motion Pictures and Filmstrips. Vol. 3. Library of Congress. 1968.

- Aitken, Ian (January 4, 2013). The Concise Routledge Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film (reprint ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-1365-1206-3.

- Albright, Thomas (August 11, 1985). Art in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945-1980: An Illustrated History. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-5200-5193-5.

- Aros, Andrew (January 1, 1977). An Actor Guide to the Talkies, 1965 Through 1974. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-1052-5.

- Castell, Ron, ed. (August 1, 1995). Blockbuster Video Guide to Movies and Videos, 1996. Dell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-4402-2114-2.

- Hinckle, Warren; Hobbs, Fredric (January 1, 1978). The Richest Place on Earth: The Story of Virginia City, and the Heyday of the Comstock Lode. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-3952-5348-9.

- Means, Howard (April 12, 2016). 67 Shots: Kent State and the End of American Innocence. Hachette Books. ISBN 978-0-3068-2379-4.

- Nash, Jay; Ross, Stanley (January 1, 1985). The Motion Picture Guide. Cinebooks. ISBN 978-0-9339-9700-4.

- Lee, Walt (January 1, 1972). Reference Guide to Fantastic Films: Science Fiction, Fantasy, & Horror. Vol. 3. Chelsea-Lee Books. ISBN 978-0-9139-7403-2.

- Thrower, Stephen (July 23, 2007). Nightmare USA: The Untold Story of the Exploitation Independents. FAB Press. ISBN 978-1-9032-5446-2.

- Welsh, James; Phillips, Gene; Hill, Rodney (August 27, 2010). The Francis Ford Coppola Encyclopedia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7651-4.

- Weldon, Michael (August 15, 1996). The Psychotronic Video Guide To Film. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-3121-3149-4.

Periodicals

- "Trojan Horse". The Art Gallery. Vol. 11. Hollycroft Press. 1967.

- "Troika". Los Angeles Free Press. Vol. 6, no. 280. November 28, 1969. p. 6. JSTOR 28039862.

- "'Troika' on Screen at Granada Theater". The Los Angeles Times. November 28, 1969. p. 26. Retrieved August 10, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Troika (Means Three)". Los Angeles Evening Citizen. November 29, 1969. p. 8. Retrieved August 20, 2023 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Troika (1969)". Red Deer Advocate. May 31, 1979. p. 50. Retrieved August 20, 2023 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Troika (1969)". Birmingham Post. September 8, 1979. p. 1. Retrieved August 20, 2023 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Troika (1969)". Edmonton Journal. December 28, 1979. p. 90. Retrieved August 20, 2023 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- Bladen, Barbra (January 29, 1971). "The Marquee". The Times. p. 13. Retrieved August 10, 2023 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- Bordwell, David (Fall 1979). "The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice". Film Criticism. 4 (1). Allegheny College: 56–64. JSTOR 44018650.

- Frankenstein, Alfred (September 19, 1965). "The Russian Little Guy Comes Through". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 26. Retrieved June 21, 2024 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- Glankoff, Mort (1969). "Untitled". Cue. Vol. 38. North American Publishing Company. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- Hale, Wanda (November 26, 1969). "Arty 'Troika' Has Limited Appeal". Daily News. p. 56. Retrieved August 10, 2023 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- Lewis, Dave (October 12, 1969). "Buckeyes Don't Rate as Playboys". Press-Telegram. p. 88. Retrieved August 10, 2023 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- Lynch, Jack (January 31, 1971). "The Essence of Filmmaker Hobbs Is an Elusive Business". The San Francisco Examiner. pp. 8–9. Retrieved August 10, 2023 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- Morch, Albert (November 7, 1969). "Games of Skill Aid Lamplighters". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 51. Retrieved April 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- Thomas, Kevin (November 27, 1969). "Fredric Hobbs Features Trilogy in His 'Troika'". The Los Angeles Times. p. 106. Retrieved August 10, 2023 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- Thomas, Kevin (December 7, 1969). "Troika". The Los Angeles Times. p. 28. Retrieved August 10, 2023 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- Thompson, Howard (November 26, 1969). "Screen: 'Troika' Arrives: Collage of Art Objects Marks Hobbs Film". New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

External links

- Troika at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Troika at AllMovie

- Troika at IMDb

- Troika at Rotten Tomatoes

- Troika at the TCM Movie Database

- Troika Press Book at the Internet Archive

- CS1 maint: url-status

- Good articles

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use mdy dates from August 2023

- 1969 films

- Template film date with 1 release date

- Pages containing links to subscription-only content

- Rotten Tomatoes ID same as Wikidata

- 1969 comedy films

- 1969 directorial debut films

- 1969 independent films

- 1960s American films

- 1960s avant-garde and experimental films

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s fantasy films

- 1960s rediscovered films

- American anthology films

- American avant-garde and experimental films

- American black-and-white films

- American independent films

- Existentialist films

- Films shot in California

- Non-narrative films

- Rediscovered American films

- Surrealist films