Sudan ebolavirus

| Sudan ebolavirus | |

|---|---|

| |

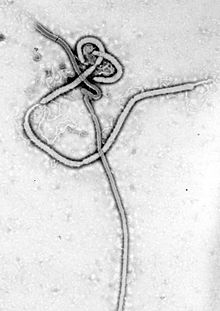

| Ebola virus under TEM | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Monjiviricetes |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Filoviridae |

| Genus: | Ebolavirus |

| Species: | Sudan ebolavirus

|

| Member virus | |

|

Sudan virus (SUDV) | |

The species Sudan ebolavirus is a virological taxon included in the genus Ebolavirus, family Filoviridae, order Mononegavirales. The species has a single virus member, Sudan virus (SUDV).[1] The members of the species are called Sudan ebolaviruses.[1] It was discovered in 1977 and causes Ebola clinically indistinguishable from the ebola Zaire strain, but is less transmissible than it. Unlike with ebola Zaire there is no vaccine available[2]

Etymology

Sudan virus (abbreviated SUDV) was first described in 1977.[3] It is the single member of the species Sudan ebolavirus, which is included into the genus Ebolavirus, family Filoviridae, order Mononegavirales.[1] The name Sudan virus is derived from South Sudan where it was first discovered before South Sudan seceded from Sudan and the taxonomic suffix virus.[4][5]

Previous designations

Sudan virus was first introduced as a new "strain" of Ebola virus in 1977.[3] Sudan virus was described as "Ebola haemorrhagic fever" in a 1978 WHO report describing the 1976 Sudan outbreak.[6]

In 2000, it received the designation Sudan Ebola virus[7][8] and in 2002 the name was changed to Sudan ebolavirus.[9][10] Previous abbreviations for the virus were EBOV-S (for Ebola virus Sudan) and most recently SEBOV (for Sudan Ebola virus or Sudan ebolavirus). The virus received its final designation in 2010, when it was renamed Sudan virus (SUDV).[1]

Reservoir

The ecology of SUDV is currently unclear, therefore, it remains uncertain how SUDV was repeatedly introduced into human populations. As of 2009, bats have been suspected to harbor the virus because infectious Marburg virus (MARV), a distantly related filovirus, has been isolated from bats,[11] traces (but no infectious particles) of the more closely related Ebola virus (EBOV) were found in bats as well.[12]

Scientists have hypothesize that humans initially become infected through contact with an infected animal such as a megabat or non-human primate.[13] Megabats are presumed to be a natural reservoir of the Ebola virus, but this has not been firmly established.[14] Due to the likely association between Ebola infection and "hunting, butchering and processing meat from infected animals", several West African countries banned bushmeat (including megabats) or issued warnings about it during the 2013–2016 epidemic though in this case the outbreak was due to Zaire ebolavirus.[15]

Taxonomy and virology

The name Sudan ebolavirus is derived from Sudan (the country in which Sudan virus was first discovered) and the taxonomic suffix ebolavirus (which denotes an ebolavirus species).[1]The species was introduced in 1998 as Sudan Ebola virus.[7][8] In 2002, the name was changed to Sudan ebolavirus.[9][10]A virus of the genus Ebolavirus is a member of the species Sudan ebolavirus if:[1]

- it is endemic in Sudan and/or Uganda

- it has a genome with three gene overlaps (VP35/VP40, GP/VP30, VP24/L)

- it has a genomic sequence different from Ebola virus by ≥30% but different from that of Sudan virus by <30%

Sudan virus (SUDV) is one of six known viruses within the genus Ebolavirus and one of the four that causes Ebola virus disease (EVD) in humans and other primates;it is the only member of the species Sudan ebolavirus.[16]

SUDV is a Select agent, World Health Organization Risk Group 4 Pathogen (requiring Biosafety Level 4-equivalent containment), National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Category A Priority Pathogen, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Category A Bioterrorism Agent.[17][18][19]

Virus inclusion criteria

A virus of the species Sudan ebolavirus is a Sudan virus (SUDV) if it has the properties of Sudan ebolaviruses and if its genome diverges from that of the prototype Sudan virus, Sudan virus variant Boniface (SUDV/Bon), by ≤10% at the nucleotide level.[1]

Molecular biology

SUDV is basically uncharacterized on a molecular level; however, its genomic sequence, and with it the genomic organization and the conservation of individual open reading frames, is similar to that of the other four known ebolaviruses. It is therefore currently assumed that the knowledge obtained for EBOV can be extrapolated to SUDV and that all SUDV proteins behave analogous to those of EBOV.[20][21]

Disease

Ebola virus disease is a viral haemorrhagic fever of humans and other primates caused by ebolaviruses.[22] Signs and symptoms typically start between two days and three weeks after contracting the virus with a fever, sore throat, muscular pain, and headaches.[22] Vomiting, diarrhoea and rash usually follow, along with decreased function of the liver and kidneys.[22] At this time, some people begin to bleed both internally and externally.[22] The disease has a high risk of death, killing 25% to 90% of those infected, with an average of about 50%.[22]

SUDV is one of four ebolaviruses that causes Ebola virus disease (EVD) in humans (in the literature also often referred to as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, EHF). EVD due to SUDV infection cannot be differentiated from EVD caused by other ebolaviruses by clinical observation alone. The strain is less transmissible than ebola Zaire.[23]

History

The first known outbreak of EVD occurred due to Sudan virus in South Sudan between June and November 1976, infecting 284 people and killing 151, with the first identifiable case on 27 June 1976.[24][25][26]In the past, SUDV has caused the following EVD outbreaks:

| Year | Geographic location | Human cases/deaths (case-fatality rate) |

| 1976 | Juba, Maridi, Nzara, and Tembura, South Sudan | 284/151 (53%)[27] |

| 1979 | Nzara, South Sudan | 34/22 (65%)[28] |

| 2000–2001 | Gulu, Mbarara, and Masindi Districts, Uganda | 425/224 (53%)[29] |

| 2004 | Yambio County, South Sudan | 17/7 (41%)[30] |

| 2011 | Luweero District, Uganda | 1/1 (100%)[31] |

| 2014 | Equateur, Congo | 0/1 * two strains reported, one Sudan and one Sudan/Zaire Hybrid to 24/08/2014(0%)[32] |

| 2022-2023 | Central and Western Regions, Uganda | 164/77 (47% confirmed and probable) [33] |

Recent outbreak

The 2022 Uganda Ebola outbreak is a current outbreak of the Ebola virus in Mubende District, Uganda. Twenty-three people are confirmed dead due to the virus, with a total of 36 of confirmed and suspected cases.[34] Uganda has previously had four outbreaks of Sudan ebolavirus; one outbreak in 2000 and 2011 and two outbreaks in 2012, as well as an outbreak of Bundibugyo virus disease in 2007 and an Ebola virus disease outbreak in 2019.[35]

The infections were decleared as an outbreak on 20 September 2022.The first cases were detected in the Mubende District among people living around a gold mine. Gold traders who move along the highway between Kampala and the Democratic Republic of the Congo may have spread it[36][37]Due to the ongoing outbreak and the fact that there is no vaccine for this strain (in contrast to Zaire ebolavirus), there is a concerted effort to bring one to market as soon as possible given the circumstances[38]

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) has appealed for emergency aid to Uganda.[39] The European Union has responded to the request with €200,000 in initial, emergency funding.[40]Due to a rapid response by authorities and public cooperation, the Ugandan government indicated on 21 October that they expect the epidemic to be over by the end of 2022.[41] On 18 November 2022, there were a total of 19 healthcare workers infected with the virus[42] On 24 November, cases were reported to be in decline.[43] On 2 December, the last individual infected with the virus was discharged from the hospital[44] On 14 December it was reported that the European Commission will send 7 million Euros to help the country in its Fight against the virus.On 20 December, all lockdowns and Ebola restrictions were lifted in the country. On 10 January, 2023 the outbreak was declared over. [45] (during the outbreak Mubende district and Kassanda district had the most cases and fatalities[46]).

Research

Vaccine

The Public Health Agency of Canada has a candidate rVSV vaccine for Sudan ebolavirus (rVSV-SUDV). Merck was developing it, but discontinued development.[47]

On 29 September , 2022 it was reported that the Ugandan government had approved an Ebola experimental vaccine trial for late October, perhaps November of this year.[48] On 1 November, 2022 three experimental Ebola vaccines were sent to Uganda per the Ministry of Health.[49]On 14 November it was reported that Remdesivir with monoclonal antibody MBP-134 were being administered to fight Sudan ebolavirus[50] The three trial vaccines for the Sudan ebolavirus are from the University of Oxford and Serum Institute of India, the Sabin Vaccine Institute and a third by Merck & Co[51][52]

ChAdOx1 biEBOV is a new vaccine that has been developed to treat both Zaire ebolavirus and Sudan ebolavirus. The new bivallent vaccine comes from Oxford Vaccine Group (40,000 doses).[53]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Kuhn, Jens H.; Becker, Stephan; Ebihara, Hideki; Geisbert, Thomas W.; Johnson, Karl M.; Kawaoka, Yoshihiro; Lipkin, W. Ian; Negredo, Ana I; et al. (2010). "Proposal for a revised taxonomy of the family Filoviridae: Classification, names of taxa and viruses, and virus abbreviations". Archives of Virology. 155 (12): 2083–103. doi:10.1007/s00705-010-0814-x. PMC 3074192. PMID 21046175.

- ↑ Ruiz, Sara I.; Zumbrun, Elizabeth E.; Nalca, Aysegul (1 January 2013). "Chapter 38 - Animal Models of Human Viral Diseases". Animal Models for the Study of Human Disease. Academic Press. pp. 927–970. ISBN 978-0-12-415894-8. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Bowen, E. T. W.; Lloyd, G.; Harris, W. J.; Platt, G. S.; Baskerville, A.; Vella, E. E. (1977). "Viral haemorrhagic fever in southern Sudan and northern Zaire, Preliminary studies on the aetiological agent". Lancet. 309 (8011): 571–3. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92001-3. PMID 65662. S2CID 3092094.

- ↑ Qureshi, Adnan I (1 January 2016). "Chapter 3 - Ebola Virus: The Origins". Ebola Virus Disease. Academic Press. pp. 23–37. ISBN 978-0-12-804230-4. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ↑ "Taxonomy browser (Sudan ebolavirus)". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ↑ "Home" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Netesov, S. V.; Feldmann, H.; Jahrling, P. B.; Klenk, H. D.; Sanchez, A. (2000). "Family Filoviridae". In van Regenmortel, M. H. V.; Fauquet, C. M.; Bishop, D. H. L.; Carstens, E. B.; Estes, M. K.; Lemon, S. M.; Maniloff, J.; Mayo, M. A.; McGeoch, D. J.; Pringle, C. R.; Wickner, R. B. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy – Seventh Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, USA: Academic Press. pp. 539–48. ISBN 978-0-12-370200-5.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Pringle, C. R. (1998). "Virus taxonomy-San Diego 1998". Archives of Virology. 143 (7): 1449–59. doi:10.1007/s007050050389. PMID 9742051. S2CID 13229117.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Feldmann, H.; Geisbert, T. W.; Jahrling, P. B.; Klenk, H.-D.; Netesov, S. V.; Peters, C. J.; Sanchez, A.; Swanepoel, R.; Volchkov, V. E. (2005). "Family Filoviridae". In Fauquet, C. M.; Mayo, M. A.; Maniloff, J.; Desselberger, U.; Ball, L. A. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy – Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, USA: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 645–653. ISBN 978-0-12-370200-5.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Mayo, M. A. (2002). "ICTV at the Paris ICV: results of the plenary session and the binomial ballot". Archives of Virology. 147 (11): 2254–60. doi:10.1007/s007050200052. S2CID 43887711.

- ↑ Towner, J. S.; Amman, B. R.; Sealy, T. K.; Carroll, S. A. R.; Comer, J. A.; Kemp, A.; Swanepoel, R.; Paddock, C. D.; Balinandi, S.; Khristova, M. L.; Formenty, P. B.; Albarino, C. G.; Miller, D. M.; Reed, Z. D.; Kayiwa, J. T.; Mills, J. N.; Cannon, D. L.; Greer, P. W.; Byaruhanga, E.; Farnon, E. C.; Atimnedi, P.; Okware, S.; Katongole-Mbidde, E.; Downing, R.; Tappero, J. W.; Zaki, S. R.; Ksiazek, T. G.; Nichol, S. T.; Rollin, P. E. (2009). Fouchier, Ron A. M. (ed.). "Isolation of Genetically Diverse Marburg Viruses from Egyptian Fruit Bats". PLOS Pathogens. 5 (7): e1000536. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000536. PMC 2713404. PMID 19649327.

- ↑ Leroy, E. M.; Kumulungui, B.; Pourrut, X.; Rouquet, P.; Hassanin, A.; Yaba, P.; Délicat, A.; Paweska, J. T.; Gonzalez, J. P.; Swanepoel, R. (2005). "Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus". Nature. 438 (7068): 575–576. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..575L. doi:10.1038/438575a. PMID 16319873. S2CID 4403209.

- ↑ "Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease): Transmission". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 17 May 2019. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ↑ "Ebola Reservoir Study". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 9 July 2018. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ↑ Zon, H.; Petesch, C. (21 September 2016). "Post-Ebola, West Africans flock back to bushmeat, with risk". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ↑ "What is Ebola Virus Disease? | Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 23 April 2021. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ↑ Bayot, Marlon L.; King, Kevin C. (2022). "Biohazard Levels". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ↑ "CDC | Bioterrorism Agents/Diseases (by category) | Emergency Preparedness & Response". emergency.cdc.gov. 15 May 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ↑ "NIAID Emerging Infectious Diseases/ Pathogens | NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases". www.niaid.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Rivera, Andrea; Messaoudi, Ilhem (November 2016). "Molecular mechanisms of Ebola pathogenesis". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 100 (5): 889–904. doi:10.1189/jlb.4RI0316-099RR. ISSN 0741-5400. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ↑ Marzi, Andrea; Banadyga, Logan (1 January 2021). "Ebola Virus (Filoviridae)". Encyclopedia of Virology (Fourth Edition). Academic Press. pp. 232–244. ISBN 978-0-12-814516-6. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 "Ebola virus disease, Fact sheet N°103, Updated September 2014". World Health Organization (WHO). September 2014. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Biryabarema, Elias (22 September 2022). "Uganda has confirmed seven Ebola cases so far, one death". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ↑ "Ebola haemorrhagic fever in Sudan, 1976" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2014.

- ↑ Feldmann, H.; Geisbert, T. W. (2011). "Ebola haemorrhagic fever". The Lancet. 377 (9768): 849–862. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60667-8. PMC 3406178. PMID 21084112.

- ↑ Hoenen T, Groseth A, Feldmann H (July 2012). "Current ebola vaccines". Expert Opin Biol Ther. 12 (7): 859–72. doi:10.1517/14712598.2012.685152. PMC 3422127. PMID 22559078.

- ↑ "Ebola haemorrhagic fever in Sudan, 1976". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 56 (2): 247–270. 1978. ISSN 0042-9686. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ↑ Baron, Roy C.; McCormick, Joseph B.; Zubeir, Osman A. (1983). "Ebola virus disease in southern Sudan: hospital dissemination and intrafamilial spread". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 61 (6): 997–1003. ISSN 0042-9686. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ↑ Okware, S. I.; Omaswa, F. G.; Zaramba, S.; Opio, A.; Lutwama, J. J.; Kamugisha, J.; Rwaguma, E. B.; Kagwa, P.; Lamunu, M. (December 2002). "An outbreak of Ebola in Uganda". Tropical Medicine and International Health. 7 (12): 1068–1075. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00944.x. ISSN 1360-2276. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ↑ "Outbreak of Ebola haemorrhagic fever in Yambio, south Sudan, April - June 2004". Releve Epidemiologique Hebdomadaire. 80 (43): 370–375. 28 October 2005. ISSN 0049-8114. Archived from the original on 8 February 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ↑ Shoemaker, Trevor; MacNeil, Adam; Balinandi, Stephen; Campbell, Shelley; Wamala, Joseph Francis; McMullan, Laura K.; Downing, Robert; Lutwama, Julius; Mbidde, Edward; Ströher, Ute; Rollin, Pierre E.; Nichol, Stuart T. (2012). "Reemerging Sudan Ebola Virus Disease in Uganda, 2011". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 18 (9): 1480–1483. doi:10.3201/eid1809.111536. ISSN 1080-6040. Archived from the original on 30 August 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ↑ "Ebola outbreak: DR Congo confirms two deaths". BBC. 24 August 2014. Archived from the original on 28 December 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ↑ "Uganda Ebola Virus Disease Situation Report No 80 - Uganda | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ "Ebola infections grow in Uganda as death toll rises to 23". CNN. 26 September 2022. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ↑ "Ebola Disease caused by Sudan virus – Uganda". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ↑ "Uganda is battling Ebola again – and the world doesn't have a vaccine | Devi Sridhar". the Guardian. 10 October 2022. Archived from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ↑ "Ebola Cases, Fatalities Rise in Uganda". VOA. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ↑ "Scientists race to test vaccines for Uganda's Ebola outbreak". www.science.org. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ↑ "Uganda, Africa: Ebola Virus Disease Emergency Appeal No. MDRUG047 - Uganda | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ↑ "Ebola outbreak: EU provides immediate support to Uganda". civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ↑ Biryabarema, Elias (21 October 2022). "Uganda says Ebola outbreak should be over by year-end". Reuters. Archived from the original on 31 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ↑ "Uganda Ebola Virus Disease Situation Report No 53 - Uganda | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. Archived from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ↑ "Uganda recording downward trend in Ebola cases - official". news.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2022. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ↑ "Uganda discharges last known Ebola patient, health ministry says". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ↑ "Uganda declares end of Ebola disease outbreak". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ↑ "Ebola Virus Disease in Uganda SitRep - 49". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Archived from the original on 20 November 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ↑ "MSF's response to CEPI's policy regarding equitable access". Médecins Sans Frontières Access Campaign. 25 September 2018. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

In vaccine development, access to know how is important. Knowledge and expertise including but not limited to purification techniques, cell lines, materials, software codes and their transfer of this to alternative manufacturers in the event the awardee discontinues development of a promising vaccine is critically important. The recent example of Merck abandoning the development of rVSV vaccines for Marburg (rVSV-MARV) and for Sudan-Ebola (rVSV-SUDV) is a case in point. Merck continues to retain vital know-how on the rVSV platform as it developed the rVSV vaccine for Zaire-Ebola (rVSV-ZEBOV) with funding support from GAVI. While it has transferred the rights on these vaccines back to Public Health Agency of Canada, there is no mechanism to share know how on the rVSV platform with other vaccine developers who would like to also use rVSV as a vector against other pathogens.

- ↑ "Ebola experimental vaccine trial may begin soon in Uganda". STAT. 29 September 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ↑ "Three experimental Ebola vaccines head to Uganda". MSN. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ↑ "The tools Uganda is using to fight Ebola outbreak". medicalxpress.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ↑ Biryabarema, Elias (8 December 2022). "Uganda receives 1,200 doses of Ebola vaccine candidates for trials". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ↑ Nelson, Millie (21 December 2022). "ReiThera supports Ebola vax production - BioProcess Insider". BioProcess International. Archived from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ↑ Sandle, Dr Tim (16 December 2022). "Rapid deployment of new bivalent Ebola vaccine to Uganda". Digital Journal. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

Further reading

- Kozlov, Max (7 October 2022). "Ebola outbreak in Uganda: how worried are researchers?". Nature: d41586–022–03192-8. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-03192-8. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- "Public health message to all NHS service providers regarding Ebola virus outbreak in Uganda (Sudan ebolavirus)". GOV.UK. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- "The U.S. response to Ebola outbreaks in Uganda". stacks.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- Ali, Urooj; Naveed, Muhammad; Ijaz, Adil; Jabeen, Khizra; Mughal, Muhammad Saad; Hasan, Jawad-ul. "The Outbreak of the Ebola Virus: Sudan Strain in Uganda and its Clinical Management". Prehospital and Disaster Medicine: 1–3. doi:10.1017/S1049023X22002199. ISSN 1049-023X. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

External links

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- Use dmy dates from August 2019

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with 'species' microformats

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Animal viral diseases

- Arthropod-borne viral fevers and viral haemorrhagic fevers

- Biological weapons

- Hemorrhagic fevers

- Ebolaviruses

- Tropical diseases

- Virus-related cutaneous conditions

- Zoonoses

- Primate diseases

- Infraspecific virus taxa