Podophyllotoxin

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Condylox, Warticon, Wartec, others |

| Other names | Podofilox,[1] (5R,5aR,8aR,9R)-9-hydroxy-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-5,8,8a,9-tetrahydrofuro[3',4':6,7]naphtho[2,3-d][1,3]dioxol-6(5aH)-one |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Main uses | Genital warts, molluscum contagiosum[2][1] |

| Side effects | Burning, pain, redness at the site of application[2] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a684055 |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Elimination half-life | 1.0 to 4.5 hours. |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H22O8 |

| Molar mass | 414.410 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 183.3 to 184 °C (361.9 to 363.2 °F) |

| |

| |

Podophyllotoxin (PPT), also known as podofilox, is a medication used to treat genital warts and molluscum contagiosum.[2][1] It is not recommended for HPV infections without external warts.[2] It is applied to the affected skin by a healthcare provider or the person themselves.[2]

Common side effects include burning, pain, and redness at the site of application.[2] It is a non-alkaloid toxin lignin extracted from Podophyllum.[3] A less refined form known as podophyllum resin is also available, but has greater side effects.[4][5]

Podophyllotoxin was first isolated in 1880.[6] It was approved for medical use in the United States in 1990.[2] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines as an alternative to podophyllum resin.[7] In the United States a bottle of 3.5 ml costs about 30 USD as of 2021.[8] It is sold under the brand names Condyline and Warticon among others.[1]

Medical uses

Podophyllotoxin cream is commonly prescribed as a potent topical antiviral.[9] It is used for the treatment of HPV infections with external warts as well as molluscum contagisum infections.[10]

Podophyllotoxin possesses a large number of medical applications. Podophyllotoxin and its derivatives are used as cathartic, purgative, antiviral agent, vesicant, antihelminthic, and antitumor agents. Podophyllotoxin derived antitumor agents include etoposide and teniposide.[11][12] These have been used in treatment of cancers including testicular, breast, pancreatic, lung, stomach, and ovarian cancers.[13]

Dosage

0.5% PPT cream is prescribed for twice daily applications for 3 days followed by 4 days with no application, this weekly cycle is repeated for 4 weeks.[15] It can also be prescribed as a gel, as opposed to cream.

Side effects

The most common side effects of podophyllotoxin cream are typically limited to irritation of tissue surrounding the application site, including burning, redness, pain, itching, swelling.[16] Application can be immediately followed by burning or itching. Small sores, itching and peeling skin can also follow, for these reasons it is recommended that application be done in a way that limits contact with surrounding, uninfected tissue[17]

Neither podophyllin resin nor podophyllotoxin lotions or gels are used during pregnancy because these medications have been shown to be embroytoxic in both mice and rats. Additionally, antimitotic agents are not typically recommended during pregnancy.[18] Additionally, it has not been determined if podophyllotoxin can pass into breast milk from topical applications and therefore it is not recommended for breastfeeding women.[19]

Podophyllotoxin cream is safe for topical use; however, it can cause CNS depression as well as enteritis if ingested. The podophyllum resin from which podophyllotoxin is derived has the same effect.[20]

Mechanism of action

Podophyllotoxin destabilizes microtubules by binding tubulin and thus preventing cell division.[21][22] In contrast, some of its derivatives display binding activity to the enzyme topoisomerase II (Topo II) during the late S and early G2 stage. For instance, etoposide binds and stabilizes the temporary DNA break caused by the enzyme, disrupts the reparation of the break through which the double-stranded DNA passes, and consequently stops DNA unwinding and replication.[23] Mutants resistant to either podophyllotoxin, or to its topoisomerase II inhibitory derivatives such as etoposide (VP-16), have been described in Chinese hamster cells.[24][25] The mutually exclusive cross-resistance patterns of these mutants provide a highly specific means to distinguish the two kinds of podophyllotoxin derivatives.[25][26] Mutant Chinese hamster cells resistant to podophyllotoxin are affected in a protein P1 that was later identified as the mammalian HSP60 or chaperonin protein.[27][28][29] Furthermore, podophyllotoxin is classified as an arytetralin lignan for its ability to bind and deactivate DNA.[30] It and its derivates bind Topo II and prevent its ability to catalyze rejoining of DNA that has been broken for replication. Lastly, experimental evidence has shown that these arytetralin lignans can interact with cellular factors to create chemical DNA adducts, thus further deactivating DNA.[30]

Chemistry

Structural characteristic

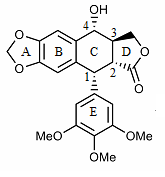

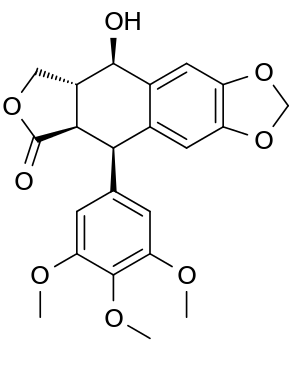

The structure of podophyllotoxin was first elucidated in the 1930s.[31] Podophyllotoxin bears four consecutive chiral centers, labelled C-1 through C-4 in the following image. The molecule also contains four almost planar fused rings. The podophyllotoxin molecule includes a number of oxygen containing functional groups: an alcohol, a lactone, three methoxy groups, and an acetal.[32]

Derivatives of podophyllotoxin are synthesized as properties of the rings and carbon 1 through 4 are diversified. For example, ring A is not essential to antimitotic activity. Aromatization of ring C leads to loss of activity, possibly from ring E no longer being placed on the axial position. In addition, the stereochemistry at C-2 and C-3 configures a trans-lactone, which has more activity than the cis counterpart. Chirality at C-1 is also important as it implies an axial position for ring E.[32]

Biosynthesis

The biosynthetic route of podophyllotoxin was not completely eludicidated for many years; however, in September 2015, the identity of the six missing enzymes in podophyllotoxin biosynthesis were reported for the first time.[33] Several prior studies have suggested a common pathway starting from coniferyl alcohol being converted to (+)-pinoresinol in the presence of a one-electron oxidant [11] through dimerization of stereospecific radical intermediate. Pinoresinol is subsequently reduced in the presence of co-factor NADPH to first lariciresinol, and ultimately secoisolariciresinol. Lactonization on secoisolariciresinol gives rise to matairesinol. Secoisolariciresinol is assumed to be converted to yatein through appropriate quinomethane intermediates,[11] leading to podophyllotoxin.

A sequence of enzymes involved has been reported to be dirigent protein (DIR), to convert coniferyl alcohol to (+)-pinocresol, which is converted by pinocresol-lariciresinol reductase (PLR) to (-)-secoisolariciresinol, which is converted by sericoisolariciresinol dehydrogenase (SDH) to (-)-matairesinol, which is converted by CYP719A23 to (-)-pluviatolide, which is likely converted by Phex13114 (OMT1) to (-)-yatein, which is converted by Phex30848 (2-ODD) to (-)-deoxypodophyllotoxin.[33] Though not proceeding through the last step of producing podophyllotoxin itself, a combination of six genes from the mayapple enabled production of the etoposide aglycone in tobacco plants.[33]

Chemical synthesis

Podophyllotoxin has been successfully synthesized in a laboratory; however, synthesis mechanisms require many steps, resulting resulted in low overall yield. It therefore remains more efficient to obtain podophyllotoxin from natural sources.[13]

Four routes have been used to synthesize podophyllotoxin with varying success: an oxo ester route,[34] lactonization of a dihydroxy acid,[35] cyclization of a conjugate addition product,[36] and a Diels-Alder reaction.[37]

History

Podophyllotoxin was first isolated in 1880 by Valerian Podwyssotzki (1818 – 28 January 1892), a Polish-Russian privatdozent at the University of Dorpat (now: Tartu, Estonia) and assistant at the Pharmacological Institute there.[38][39]

Society and culture

Natural abundance

Podophyllotoxin is present at concentrations of 0.3% to 1.0% by mass in the rhizome of the American mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum).[23][40] Another common source is the rhizome of Sinopodophyllum hexandrum Royle (Berberidaceae).

It is biosynthesized from two molecules of coniferyl alcohol by phenolic oxidative coupling and a series of oxidations, reductions and methylations.[23]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Podophyllotoxin for anogenital warts; Podophyllotoxin info". patient.info. Archived from the original on 2018-05-07. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "Podofilox". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Xu H, Lv M, Tian X (2009). "A review on hemisynthesis, biosynthesis, biological activities, mode of action, and structure-activity relationship of podophyllotoxins: 2003-2007". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (3): 327–49. doi:10.2174/092986709787002682. PMID 19149581.

- ↑ "Podophyllum Resin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 307. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ↑ Cragg GM, Kingston DG, Newman DJ (2011). Anticancer Agents from Natural Products, Second Edition (2 ed.). CRC Press. p. 97. ISBN 9781439813836. Archived from the original on 2021-07-01. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ↑ "Condylox Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips - GoodRx". GoodRx. Archived from the original on 29 September 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ↑ Ardalani, H; Avan, A; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M (2016). "Podophyllotoxin: a novel potential natural anticancer agent". Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine. 7 (4): 285–294. PMC 5580867. PMID 28884079.

- ↑ Ardalani, H; Avan, A; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M (2016). "Podophyllotoxin: a novel potential natural anticancer agent". Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine. 7 (4): 285–294. PMC 5580867. PMID 28884079.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Gordaliza M, García PA, del Corral JM, Castro MA, Gómez-Zurita MA (September 2004). "Podophyllotoxin: distribution, sources, applications and new cytotoxic derivatives". Toxicon. 44 (4): 441–59. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.05.008. PMID 15302526.

- ↑ Damayanthi Y, Lown JW (June 1998). "Podophyllotoxins: current status and recent developments". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 5 (3): 205–52. PMID 9562603.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Canel C, Moraes RM, Dayan FE, Ferreira D (May 2000). "Podophyllotoxin". Phytochemistry. 54 (2): 115–20. doi:10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00094-7. PMID 10872202.

- ↑ Liu YQ, Tian J, Qian K, Zhao XB, Morris-Natschke SL, Yang L, Nan X, Tian X, Lee KH (January 2015). "Recent progress on C-4-modified podophyllotoxin analogs as potent antitumor agents". Medicinal Research Reviews. 35 (1): 1–62. doi:10.1002/med.21319. PMC 4337794. PMID 24827545.

- ↑ "Podofilox Monograph for Professionals - Drugs.com". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2016-12-21. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- ↑ Longstaff E, von Krogh G (April 2001). "Condyloma eradication: self-therapy with 0.15-0.5% podophyllotoxin versus 20-25% podophyllin preparations--an integrated safety assessment". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 33 (2): 117–37. doi:10.1006/rtph.2000.1446. PMID 11350195.

- ↑ "PRODUCT INFORMATION WARTEC® SOLUTION" (PDF). GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ↑ Sundharam JA (July 1989). "Is Podophyllin Safe for Use in Pregnancy?". Archives of Dermatology. 125 (7): 1000–1. doi:10.1001/archderm.1989.01670190134022. PMID 2742385.

- ↑ "Podophyllotoxin | DermNet New Zealand". www.dermnetnz.org. Archived from the original on 2018-05-07. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- ↑ Moher LM, Maurer SA (August 1979). "Podophyllum toxicity: case report and literature review". The Journal of Family Practice. 9 (2): 237–40. PMID 458391.

- ↑ Hamidreza A, Amir A, Majid G (2017-06-01). "Podophyllotoxin: a novel potential natural anticancer agent". Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine. 7 (4). doi:10.22038/ajp.2017.8779. S2CID 2231369.

- ↑ Gordaliza M, Castro MA, del Corral JM, Feliciano AS (December 2000). "Antitumor properties of podophyllotoxin and related compounds". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 6 (18): 1811–39. doi:10.2174/1381612003398582. PMID 11102564.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Canel C, Moraes RM, Dayan FE, Ferreira D (2000). "Molecules of Interest: Podophyllotoxin". Phytochemistry. 54 (2): 115–120. doi:10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00094-7. PMID 10872202.

- ↑ Gupta RS, Ho TK, Moffat MR, Gupta R (January 1982). "Podophyllotoxin-resistant mutants of Chinese hamster ovary cells. Alteration in a microtubule-associated protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 257 (2): 1071–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)68309-2. PMID 7054166.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Gupta, R.S. (1983). "Genetic, biochemical and cross-resistance studies with mutants of Chinese hamster ovary cells resistant to the anticancer drugs VM-26 and VP16-213". Cancer Res. 43 (4): 1568–1574. PMID 6831403.

- ↑ Gupta RS (February 1983). "Podophyllotoxin-resistant mutants of Chinese hamster ovary cells: cross-resistance studies with various microtubule inhibitors and podophyllotoxin analogues". Cancer Research. 43 (2): 505–12. PMID 6848174.

- ↑ Picketts DJ, Mayanil CS, Gupta RS (July 1989). "Molecular cloning of a Chinese hamster mitochondrial protein related to the "chaperonin" family of bacterial and plant proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 264 (20): 12001–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)80166-1. PMID 2568357.

- ↑ Jindal S, Dudani AK, Singh B, Harley CB, Gupta RS (May 1989). "Primary structure of a human mitochondrial protein homologous to the bacterial and plant chaperonins and to the 65-kilodalton mycobacterial antigen". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 9 (5): 2279–83. doi:10.1128/mcb.9.5.2279. PMC 363030. PMID 2568584.

- ↑ Trevor AJ, Katzung BG, Kruidering-Hall M, Masters SB (2013). "Chapter 54: Cancer Chemotherapy". Pharmacology examination & board review (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-178923-3.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Botta B, Delle Monache G, Misiti D, Vitali A, Zappia G (September 2001). "Aryltetralin lignans: chemistry, pharmacology and biotransformations". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 8 (11): 1363–81. doi:10.2174/0929867013372292. PMID 11562272.

- ↑ Borsche W, Niemann J (1932). "Über Podophyllin". Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 494: 126–142. doi:10.1002/jlac.19324940113.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 You Y (2005). "Podophyllotoxin derivatives: current synthetic approaches for new anticancer agents". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 11 (13): 1695–717. doi:10.2174/1381612053764724. PMID 15892669.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Lau W, Sattely ES (September 2015). "Six enzymes from mayapple that complete the biosynthetic pathway to the etoposide aglycone". Science. 349 (6253): 1224–8. Bibcode:2015Sci...349.1224L. doi:10.1126/science.aac7202. PMC 6861171. PMID 26359402.

- ↑ Kende AS, King ML, Curran DP (June 1981). "Total synthesis of (.+-.)-4'-demethyl-4-epipodophyllotoxin by insertion-cyclization". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 46 (13): 2826–2828. doi:10.1021/jo00326a056.

- ↑ Macdonald DI, Durst T (August 1988). "A highly stereoselective synthesis of podophyllotoxin and analogues based on an intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 53 (16): 3663–3669. doi:10.1021/jo00251a003.

- ↑ Ziegler FE, Schwartz JA (March 1978). "Synthetic studies on lignan lactones: aryl dithiane route to (.+-.)-podorhizol and (.+-.)-isopodophyllotoxone and approaches to the stegane skeleton". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 43 (5): 985–991. doi:10.1021/jo00399a040.

- ↑ Klemm LH, Olson DR, White DV (December 1971). "Intramolecular Diels-Alder reactions. VII. Electroreduction of .alpha.,.beta.-unsaturated esters. I. Synthesis of rac-deoxypicropodophyllin by intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction plus trans addition of hydrogen". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 36 (24): 3740–3743. doi:10.1021/jo00823a017.

- ↑ See:

- Podwyssotzki, Valerian (1880). "Pharmakologische Studien über Podophyllum peltatum" [Pharmacological studies of Podophyllum peltatum]. Archiv für experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie (in German). 13: 29–52. Archived from the original on 2021-06-08. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) Podwyssotzki named podophyllotoxin on p. 30: " … ich nenne sie bis auf weiteres Podophyllotoxin." ( … for the time being I call it "podophyllotoxin".) - Podwyssotzki, Valerian (10 September 1881). "The active constituents of podophyllotoxin". Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions. 3rd series. 12: 217–219. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- Podwyssotzki, Valerian (March 1882). "On the active constituents of podophyllin". American Journal of Pharmacy. 54: 102–115. Archived from the original on 2021-06-08. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- Podwyssotzki, Valerian (1882). "Über die wirksamen Bestandtheile des Podophyllins" [On the active components of podophyllin]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 15: 377–378. Archived from the original on 2021-06-08. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Obituary: Kobert, Rudolph (February 1893). "Valerian Podwyssotzki". Bulletin of Pharmacy. 7 (2): 49–52. Archived from the original on 2021-06-15. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- Podwyssotzki, Valerian (1880). "Pharmakologische Studien über Podophyllum peltatum" [Pharmacological studies of Podophyllum peltatum]. Archiv für experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie (in German). 13: 29–52. Archived from the original on 2021-06-08. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ Shah, Zinnia; Gohar, Umar Farooq; Jamshed, Iffat; Mushtaq, Aamir; Mukhtar, Hamid; Zia-UI-Haq, Muhammad; Toma, Sebastian Ionut; Manea, Rosana; Moga, Marius; Popovici, Bianca (April 2021). "Podophyllotoxin: history, recent advances and future prospects". Biomolecules. 11 (4): 603. doi:10.3390/biom11040603. PMC 8073934. PMID 33921719.

- ↑ Hartwell JL, Schrecker AW (1951). "Components of Podophyllin. V. The Constitution of Podophyllotoxin". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 73 (6): 2909–2916. doi:10.1021/ja01150a143.

External links

- Kelly M, Hartwell JL (February 1954). "The biological effects and the chemical composition of podophyllin: a review". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 14 (4): 967–1010. PMID 13233838.

- Hartwell JL, Schrecker AW (1951). "Components of Podophyllin. V. The Constitution of Podophyllotoxin". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 73 (6): 2909–2916. doi:10.1021/ja01150a143.

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: unrecognized language

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugs with no legal status

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Articles with changed DrugBank identifier

- World Health Organization essential medicines (alternatives)

- Berberidaceae

- Antiviral drugs

- Lignans

- Phenol ethers

- Gamma-lactones

- Furonaphthodioxoles

- Plant toxins

- RTT