Mother Solomon

Margaret Grey Eyes Solomon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 1816 |

| Died | August 18, 1890 (aged 73) Wyandot County, Ohio, U.S. |

| Resting place | Wyandot Mission Church |

| Other names | Mother Solomon |

| Occupation | Nanny |

| Spouses | David Young

(m. 1833; died 1851)John Solomon

(m. 1860; died 1876) |

| Children | 8 |

| Signature | |

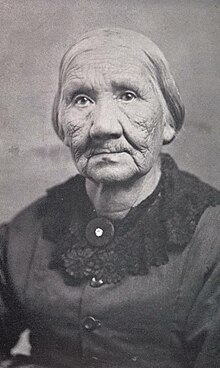

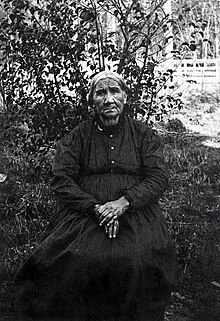

Margaret Grey Eyes Solomon (November 1816 – August 18, 1890), better known as Mother Solomon, was a Wyandot nanny. Born along Owl Creek, Ohio, her father took her to Indigenous sites like the Olentangy Indian Caverns as a child. After moving to the Big Spring Reservation in 1822, she learned housekeeping and English at a mission school. By age eight, Solomon began attending the Wyandot Mission Church. Two of her children with David Young, who she married in 1833, were buried in its grounds. In 1842, her community succumbed to the Indian Removal Act and signed a treaty to move to Kansas. Solomon and hundreds of Wyandots met at the church the following July to commemorate. Dozens died of illness along the journey, and in Kansas, Solomon sought to protect the Huron Indian Cemetery, as by 1860, she had buried within it her husband and six remaining children. Whilst in Kansas, $865 worth of belongings,[a] including oxen, pigs, and horses, were stolen from her.

Margaret became homesick after marrying John Solomon. In 1865, alongside her nephew, they relocated to her prior home in Ohio. When John died in 1876, Margaret began babysitting children. She garnered the nickname "Mother Solomon", and many residents later attested to being raised by her. Solomon told the children traditional stories and demonstrated the Wyandot language at community gatherings. She also advocated for the run-down mission church to be restored. During its rededication in 1889, she sang "Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing" in Wyandot. Many onlookers were struck by the language. In her final years, Solomon sensed she was weakening. She died in 1890, and her funeral at the mission church was widely attended. The Wyandot County Museum has since displayed her belongings, and in 1984, the archivist Thelma R. Marsh published her biography.

Early life, education, and family

Margaret Grey Eyes Solomon was born in November 1816 along Owl Creek in Marion County, Ohio.[2][b] The oldest of at least four siblings and two half-siblings,[3][5] her father was the Wyandot chief John "Squire" Grey Eyes,[2][6][c] and her mother was named Eliza.[7] Following tradition, Eliza pierced Solomon's ears a few days after birth and inserted chicken feathers to maintain the holes. Eliza anticipated that she would wear jewelry. Solomon only received her given name upon the Green Corn Feast held in August.[8] At age four, she and Squire went to Hancock County on a hunting trip. They traveled the 50 miles by horse, and while there, Solomon spotted many rabbits. They camped one night at Fort Findlay in a blockhouse built for president William Henry Harrison.[9][10] That year, Squire also accompanied Solomon to the Olentangy Indian Caverns. She was too afraid to explore them, but realized the importance of visiting such sites where her ancestors had held meetings or hid from enemies.[11]

Solomon and her family, busy hunting and trading along village footpaths, moved to the Big Spring Reservation in 1822.[3][11] She began reciting traditional Wyandot language teachings to her dolls,[12] and enacted a tea party with them by an oak tree when she was still five, with acorns for cups. Squire noticed and played along before sending her to help Eliza in the garden.[13] Solomon's uncle, chief Warpole, often visited their home to tell stories. Before he arrived that day, Eliza prepared a squirrel stew dinner. Solomon then sat with her siblings to hear Warpole recount their "Grey Eyes" lineage. He spoke of customs like the war dance, Green Corn Feast, and lacrosse and highlighted the community's tobacco-growing origins in Canada.[14][15]

Methodist missionaries were prominent in the reserve and informed the theological practices of many Wyandots; Squire was among a group of chiefs that requested the Methodist Episcopal Church to build a mission school in neighboring Upper Sandusky.[16] Upon its opening in 1821, Solomon was one of the first students to be enrolled.[2] She became the "little charge" of Harriet Stubbs, who taught her hymns,[17] and a friend of John Stewart, who taught her to read and write English.[18] Alongside the other schoolgirls, she learned to cook, sew, assemble fibers for knitting, and housekeep.[3][6] Stewart died of illness in December 1823, which saddened her,[18] yet she continued to attend the school, all the while its number of facilities increased.[2][19] Missionaries often visited Squire at home, and Solomon enjoyed preaching and singing with them.[20]

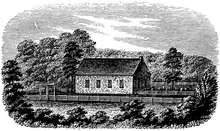

A religious vigor pervaded Solomon at school.[6] She began attending the nearby Wyandot Mission Church at age eight.[21] Solomon then befriended each of its pastors.[2] She also began sharing the gospel with her community. Owing to this, some Wyandots buried around the church were her converts.[6] As a young woman, Solomon remained at the school to help its children, and David Young, a Wyandot friend and classmate, invited her on a date. They paddled along the Sandusky River after she received Eliza's permission.[22] On February 4, 1833, the couple were married in the church by the priest Thomas Simms.[23] They moved into a log cabin Young had built over the river.[24]

Wyandot removal to Kansas

President Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Act, calling for Indigenous communities to move west of the Mississippi River, passed in 1830.[25] The Wyandots faced mounting pressure as treaty commissioners, spurred on by federal government, began to entice removal within the region, and nearby Lenapes and Shawnees signed their own removal treaties. However, Wyandot scouting parties out west in 1831 and 1834 rejected their proposed land tracts.[26] Tensions peaked in the fall of 1841 when two white men murdered the head chief Summundewat, rendering Solomon uncertain as to her community's future.[27][28] She tried convincing her leaders to valedict their homeland;[29] Squire only conceded when a Wyandot council voted two-thirds in favor of removal. After securing 25,000 acres within Kansas City, Kansas, the Wyandots signed a removal treaty in March 1842.[30]

On July 12, 1843, hundreds gathered at the Wyandot Mission Church, Solomon included, to "sob their last farewells", disperse flowers across the adjoining graveyard, and hear Squire give a farewell speech in the Wyandot language.[31][32] Solomon hugged Mrs. Parker, a white neighbour, and David Young shook hands with his white friends.[33] They had two children of their own buried in the cemetery,[34] but remained with a son and two daughters, the youngest of whom rode in a cradleboard upon Solomon's back.[33] About 664 Wyandots arrived in Cincinnati, Ohio, after a week of travel by wagon, horse, and foot. Before boarding two steamships, they were harassed by whiskey traders. They learned that their land had been reneged upon setting foot in Kansas, forcing many to camp in the flooded lowlands. Blinding eye inflammation, measles, and severe diarrhea were widespread, and 18% of the initial Wyandot fleet had died by 1844.[35]

Having endured the traumatic journey, Young began work as a ferryman while Solomon tried to recuperate with her family.[36] In the spring, she began an apple tree orchard and a garden. They were unfenced, and she had to fend of her neighbour's pigs.[37] Solomon had a few more children,[36] totaling to eight, but alongside the remaining ones, these died in infancy.[3] Upon the death of her two-year-old son in 1848 and another son to fever a year later, she only had three living daughters by 1851. That year, Young contracted fatal tuberculosis, and in 1852, another daughter died. By the end of the decade, Solomon had buried her entire family side by side in the Huron Indian Cemetery, which had replaced the mission school and church as a Wyandot bastion.[36][38] Her community's legal status, threatened by forced enfranchisement, settled into limbo, so she had to continuously demonstrate the importance of the graveyard. Even after returning to Ohio, the year she died, Solomon signed a document objecting to the removal of the cemetery's remains.[39]

A gray horse, bay horse, and brown mare, worth $195 combined,[d] were stolen from Solomon in September 1848, of which she attributed to Oregon emigrants. Further thefts occurred that fall to 30 of her pigs, worth $90 in total.[e] A friend of hers, Catherine Johnson, corroborated that possessions totaling $580,[f] including oxen and horses, were stolen from her across 1855–1859. In one case, a housekeeper named James Cook fled after taking $225 of gold coin from a chest owned by her brother.[40][g] However, in 1860, Margaret reportedly "found new happiness" when she married the Wyandot sheriff John Solomon.[41][42][h] He was likewise a widow.[41]

Return to Ohio

Margaret was struck by homesickness after marrying John.[2][43] A longing formed for her old memories, as well as her children buried by the Wyandot Mission Church. This compelled her to address a letter to the government requesting permission to return to Ohio. Once it was accepted,[29] she convinced John and her nephew, Jimmy Guyami, to join her.[2] In October 1862, her and John's two-acre land tract on the south end of Tauromee Street was put up for auction,[44] and in 1865, the three returned to Upper Sandusky.[2]

Upon arrival, Margaret and John became members of the Belle Vernon United Brethren Church, whose services took place in a schoolhouse. John also took up a job as a tailer. New shops, hotels, and a large courthouse now stood downtown. However, they settled along the Big Spring Reservation in the small cabin David Young had built.[2][45] Much of the original village had deteriorated. The community council house burned down in 1851, and the roof and walls of the mission church had begun to collapse.[43] Even so, a few former houses remained among the 2,500 residents.[43][46] Margaret reunited with Mrs. Parker, who still lived in a brick home with her family. The Parker Covered Bridge was built beside them in 1873, which Margaret and John frequently wandered across during their trips to Upper Sandusky.[47]

John died on December 14, 1876, widowing Margaret a second time.[3][48] Now 60, she found pleasure in babysitting the neighbourhood children,[2] for which she often sought after struggling families.[43] She also became a surrogate mother.[2] The historian Kathryn Magee Labelle described her childcare as "tireless [and] daily",[49] and the village nicknamed her "Mother Solomon" out of respect. Many residents later attested to being raised by her, and some deemed it an honor.[2][43] According to James F. Croneis of Telegraph-Forum, one woman affirmed as late as the 1950s that Solomon had cared for her.[50] Solomon used her good reputation to promote Wyandot culture and teachings amongst the village. She continued to speak the language and demonstrated it during community gatherings and public presentations. To remind children of the ties between their ancestors and contemporary Wyandots, Solomon repeated traditional stories told to her by elders.[51] The Hocking Sentinel described her storytelling as "full of interest and romance". They thought she displayed "a wonderful amount of intelligence" on the topic of the genealogy of her ancestors whom, as she described, lived near Lake Huron, were termed "Petun" by the French for their harvesting of tobacco, and faced attack by the Iroquois.[52] In 1881, Solomon took a train to and from Kansas to visit her relatives, who had sent many invitations. Guyami looked after her chickens and cows while she was away.[3][53] In 1883, she gave away paintings of the prominent chiefs Mononcue and Between-the-Logs, permitting them to be reproduced.[54]

Solomon implored the village to restore and continue operating the run-down mission church. She argued that by doing so, a piece of the Ohian-Wyandot historical record would be preserved. In 1888, having set aside a $2,000 budget, the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church began repairs.[12] Upon completion, on September 21, 1889, the Central Ohio Conference held a rededication ceremony.[12][55] There were an estimated 3,000 attendees that afternoon, Guyami included.[55][56] William H. Gibson was among the various ministers who gave speeches,[57] and Elnathan C. Gavitt, the only former missionary in attendance, spoke of the church's accomplishments.[58] Likewise, Solomon was the only departing Wyandot of 1843 to be present.[12][57] At the age of 72, she "delight[ed] the audience" with a Wyandot translation of "Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing", a hymn she had learned there.[34] The Urbana Daily Citizen's J. W. Henley called her an "object of great interest",[55] to which the Western Christian Advocate agreed.[58] She was described as "aged and venerable",[57] yet "strong and well preserved".[58] Many attendees admired the beauty of her native language,[34] and The Bryan-College Station Eagle thought she sang in a "sweet, clear voice".[56] As the participants of the service circulated and shook hands, the Western Christian Advocate concluded: "Mother Solomon, and many others, became very happy, and rejoiced, and shouted the praises of God."[58]

In her final years, Solomon sensed that she was weakening.[2] When the Sandusky River flooded her cabin, a townsman named Joseph Parker would row over and retrieve her from the upstairs window.[59] N. B. C. Love, an organizer of the mission church's rededication,[57] reported in 1889: "Native to this soil, she expects before many years to lie down in it, as in the arms of a loving mother, while with the Christian's hope she sings of 'The Land That Is Fairer than Day,' where she expects to meet the loved ones of her people."[60] By July 1890, she agreed to move into the home of Mr. and Mrs. Jacob Hayman.[2]

Death and legacy

Solomon died on August 18, 1890. Her funeral was held in the Wyandot Mission Church two days later.[2][61] Despite a downpour that morning, a large crowd with "pioneers from all parts of the county" gathered to pay their respects. The service was led by the paster G. Lease, who spoke of her "nobleness and true womanhood".[61][62] Solomon was buried next to her husband David Young in the fenced cemetery behind the church.[2] Her death was widely reported in local newspapers, which emphasized her father as a noted chief, her removal to Kansas and return to Ohio, and her respected work as a nanny. The historian Kathryn Magee Labelle referred to this coverage as a "momentary acknowledgement of [Wyandot] resilience in Ohio". However, many stories distorted Solomon as "the last of the Wyandots", which she attributed to the prominent "Vanishing Indian" stereotype and an attempt at erasing Wyandots from Ohio.[61] Solomon has since been deemed a popular Ohian figure. According to the archivist Thelma R. Marsh,[7] she was "almost a legend" when she died.[63] Labelle wrote that her attainment of the honorific "Mother", as opposed to the lesser "Sister" or "Auntie", indicated that her work was successful. She ascribed Solomon to a Midwestern, 19th century wave of mothers who sought to mediate between settler and Indigenous groups.[49] Similarly, in the encyclopedia Women of Ohio, it is doubted that an Indigenous or White woman was more "admired and trusted" by either race than Solomon.[6]

In February 1931, a century-old chair built by Solomon, with a woven shagbark hickory seat and no nails, was displayed at the Wyandot County Museum.[64] They dedicated a glass case to her in May 1971, which exhibited her glasses, smoking pipe, beaded purse, candle molds, woven basket, and portrait.[65] An exception to Solomon's limited bibliography is Marsh's 1984 children's book Daughter of Grey Eyes: The Story of Mother Solomon. It spans 60 pages and draws from archival material, journal articles, and family interviews.[7] On the morning of August 12, 1990, Marsh led a service at the mission church commemorating the centennial of Solomon's funeral.[66] She died and was buried there two years later.[7] In October 2016, the church held a tour of the cemetery during an event celebrating the bicentennial of missionaries coming to Ohio. Solomon's life, among others, was recounted to the 192 people in attendance.[67] After the McCutchen Overland Inn Museum received Solomon's saddle from the Wyandot County Museum, they displayed it among the Anderson General Store in May 2021.[68]

Notes

- ^ Equivalent to $21,000 in 2023.[1]

- ^ Thelma R. Marsh, The Cincinnati Enquirer, and Ronald I. Marvin Jr. cite November 26, 27, and 29, respectively, as her birthdate.[2][3][4] The Cincinnati Enquirer cites Wayne County as her birthplace.[3]

- ^ Kathryn Magee Labelle cites "Lewis" as his given name. Variations on the surname include "Greyeyes" and "Grey-Eyes",[7] sometimes with the spelling "Gray".[3]

- ^ Equivalent to $4,700 in 2023.[1]

- ^ Equivalent to $2,200 in 2023.[1]

- ^ Equivalent to $14,000 in 2023.[1]

- ^ Equivalent to $5,400 in 2023.[1]

- ^ Marvin Jr. and The Cincinnati Enquirer cite 1858 as the year of marriage.[2][3]

References

- ^ a b c d e 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Marvin Jr. 2015, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Mother Solomon. Last of the Wyandot Indian Tribe in This State". The Cincinnati Enquirer. September 29, 1889. p. 19. Archived from the original on April 8, 2024. Retrieved April 8, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Marsh 1984, p. 1.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b c d e Neely 1939, p. 59.

- ^ a b c d e Labelle 2021, p. 53.

- ^ Marsh 1984, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Marsh 1984, pp. 3, 5.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 3–5.

- ^ a b Labelle 2021, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d Labelle 2021, p. 63.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Marsh 1984, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 53, 62–63.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Stevenson, R. T. (January 12, 1916). "Centennial of the Wyandot Mission: 1816-1916". Western Christian Advocate. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 21, 2024. Retrieved April 21, 2024 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- ^ a b Marsh 1984, p. 17.

- ^ Labelle 2021, p. 57.

- ^ Marsh 1984, p. 20.

- ^ Marsh 1984, p. 23.

- ^ Marsh 1984, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Labelle 2021, p. 54.

- ^ Marsh 1984, p. 26.

- ^ Labelle 2021, p. 51.

- ^ Littlefield Jr. & Parins 2011, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Marsh 1984, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Labelle 2021, p. 59.

- ^ a b Neely 1939, p. 60.

- ^ Labelle 2021, p. 58.

- ^ Marsh 1984, p. 33.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 52, 59.

- ^ a b Marsh 1984, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Labelle 2021, p. 64.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 59–61.

- ^ a b c Labelle 2021, p. 61.

- ^ Marsh 1984, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Marsh 1984, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Report of the Commissioners Appointed in Accordance with the Senate Amendment of the 13th Article of the Treaty of 23d of February, 1867, Embracing the Claims of the Wyandott Indians. Index to the Senate Executive Documents for the Second Session of the Forty-First Congress of the United States of America. 1869–'70. (Report). Vol. 2. United States Government Printing Office. 1870. pp. 12–13. Retrieved April 27, 2024.

- ^ a b Marsh 1984, p. 41.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 52, 64.

- ^ a b c d e Labelle 2021, p. 62.

- ^ Wood, Luther H. (May 25, 1862). "Sheriff's Sale". The Olathe News. p. 3. Archived from the original on May 1, 2024. Retrieved April 30, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Marsh 1984, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Marsh 1984, p. 42.

- ^ Marsh 1984, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Marsh 1984, p. 44.

- ^ a b Labelle 2021, p. 52.

- ^ Croneis, James F.; et al. (September 6, 1991). "A Short History of the Indians of Crawford and Wyandot Counties (Part 23)". Telegraph-Forum. p. 4. Archived from the original on April 8, 2024. Retrieved April 8, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 62–63.

- ^ "The Last of the Wyandottes". The Hocking Sentinel. September 4, 1890. p. 2. Archived from the original on May 4, 2024. Retrieved May 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Marsh 1984, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Schlup, Emil (April 1906). "The Wyandot Mission". Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications. 15: 169, 177. Archived from the original on May 4, 2024. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c Henley, J. W. (September 25, 1889). "Rev. J. W. Henley Describes the City and the M. E. Conference Recently Held There". Urbana Daily Citizen. p. 3. Archived from the original on May 5, 2024. Retrieved May 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Famous Old Church". Bryan-College Station Eagle. June 11, 1897. p. 2. Archived from the original on May 5, 2024. Retrieved May 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d King, I. F. (October 1901). "Introduction of Methodism in Ohio". Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications. 10: 203. Archived from the original on May 5, 2024. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c d B., T. N. (October 2, 1889). "Re-dedication of the Wyandot Mission Church". Western Christian Advocate. p. 4. Archived from the original on May 5, 2024. Retrieved May 5, 2024 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- ^ Marsh 1984, p. 46.

- ^ Love, N. B. C. (March 5, 1889). "The Exodus of the Wyandots". Telegraph-Forum. p. 4. Archived from the original on May 6, 2024. Retrieved May 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Labelle 2021, p. 65.

- ^ "Last of the Wyandots". Cincinnati Commercial Gazette. August 20, 1890. p. 2. Archived from the original on May 8, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- ^ "Wyandotte Indian Tribe Gets Paid for ¼ of Ohio". Dayton Daily News. February 17, 1985. p. 13. Archived from the original on May 8, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Indian Chair 100-Years Old". East Liverpool Review. February 12, 1931. p. 8. Archived from the original on May 8, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- ^ Mathern, Jeanette (May 19, 1971). "Museum Inspires Recollections of Yesterday". Carey Progressor. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 8, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- ^ "Mother Solomon Funeral to Be Remembered Sunday". Telegraph-Forum. August 11, 1990. p. 3. Archived from the original on May 8, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Labelle 2021, p. 66–67.

- ^ Wolf, Jeannie Wiley (July 13, 2021). "Overland Inn Museum Reopens Century-Old General Store". The Courier. Archived from the original on May 8, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

Bibliography

- Neely, Ruth, ed. (1939). Women of Ohio: A Record of Their Achievements in the History of the State. Vol. 1. S. J. Clarke Publishing Company. OCLC 1012031260.

- Marsh, Thelma R. (1984). Daughter of Grey Eyes: The Story of Mother Solomon. OCLC 11815829.

- Littlefield Jr., Daniel F.; Parins, James W., eds. (2011). Encyclopedia of American Indian Removal. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-36042-8. OCLC 720586004.

- Marvin Jr., Ronald I. (2015). A Brief History of Wyandot County, Ohio. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-62585-535-0. OCLC 951076427.

- Labelle, Kathryn Magee (March 2021). Daughters of Aataentsic: Life Stories from Seven Generations. McGill–Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-228-00688-6. OCLC 1200316007.