Luxembourg and the Belgian Revolution

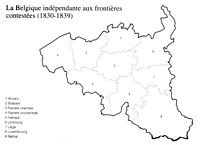

In the early 19th century, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg was ruled in personal union by the King of the Netherlands, William I. The territory that is now Belgium was similarly part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. When the Belgian Revolution occurred in 1830, most of Luxembourg rallied to this Revolution, and accepted Belgian rule. The exception was the fortress and capital, Luxembourg City, which housed a Dutch-German garrison and remained loyal to William I. This led to a de facto separation of the country from 1830-1839, when most of it was loyal to and administered by Belgium, while one part retained allegiance to the Netherlands. The situation was resolved in 1839 when the international great powers and William I agreed that Luxembourg would remain in his possession, and lose its French-speaking parts to the new country of Belgium.

Background

At the Vienna Congress of 1815, the great powers of Europe awarded Luxembourg to the Dutch King as his personal possession. Unlike the Netherlands, Luxembourg would also be part of the German Confederation. While it was meant to be a sovereign country in its own right, William I treated it as a province of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.[1] The Dutch constitution and laws were introduced in Luxembourg, Dutch officials were sent there, and in 1823 the Dutch language was made obligatory in its courts.[2]

Before 1841, Luxembourgers were considered Dutch citizens.[3] Luxembourg's foreign and military affairs were managed by the Dutch Ministries of Foreign Affairs and of War, respectively. Luxembourgers travelling abroad did so with Dutch passports.[3]

The United Kingdom of the Netherlands at the time included the present-day Netherlands and present-day Belgium. Likewise, the Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg was twice as big as currently, as it also included what is now the Belgian province of Luxembourg.

1830-1839: de facto divided country

The period from 1830 to 1839 is considered a challenging one in the history of Luxembourg. It was one of the poorest regions in Europe, lacking infrastructure, and characterised by subsistence agriculture and run-down small industrial establishments.[4]

When the Belgian provinces, unhappy with William I's rule, rose up in rebellion, the Luxembourgers joined them. The provisional government formed in Brussels declared Luxembourg to be an integral part of Belgium, and claimed authority over it.[1] In the whole country, except the capital, Belgian administration was exercised.[1] The Belgians levied taxes, provided the police, and administered justice through courts of law.[5] It was governed by a Belgian governor, whose seat was in Arlon.[6] The Belgian constitution of 7 February 1831 included the entire Grand-Duchy as one of the nine provinces of Belgium.[7]

However, the fortress and capital city of Luxembourg, unable to follow suit, led to the division of the country. The territory outside the fortress came under complete Belgian administration, while the Dutch regime, supported by the Dutch-Prussian garrison, retained control in the capital. From the 1830 to 1830, a state of cold war existed between the Belgian and Dutch administrations; both sides sought to gain advantages through minor skirmishes, abductions of individuals, and incarcerations of individuals with the possibility of prisoner exchanges.[5][4] These, and the risk of war, and general uncertainty about the future created an atmosphere of insecurity and fear in the population.[5][4]

During this decade, the fortress walls arbitrarily separated a population that rejected the political partition of its homeland. The historian Christian Calmes made a comparison with the Berlin Wall, and the arrangements on both sides governing contacts between the populations of the two Germanys.[4]

In Luxembourg, the majority of the common people, who had nothing to lose, and a significant portion of the leadership were drawn into the "pull" created by the Belgian Constitution and the hope that the new state centered around Brussels inspired on all fronts.[4]

Press

The events of the Belgian Revolution provided a huge stimulus to political debates in Luxembourg, and these debates echoed in the press. The Journal de la ville et du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, published in Luxembourg City, was Orangist in its editorial line, loyal to the government and King-Grand Duke and the German Confederation. It was also the only newspaper officially tolerated by the government. It would soon, however, no longer hold a monopoly.[8]

When the Revolution started, the Journal staunchly defended the policy of William I and entered into competition with the Journal d'Arlon.[8]

Benefiting from the freedom of the press guaranteed in the liberal Belgian Constitution, this bi-weekly liberal newspaper with liberal tendencies, led by Luxembourger François Dubois, became far more popular than the Orangist Journal of Luxembourg City.[8]

General Goedecke, the head of Luxembourg's armed forces under William I, prohibited the Luxembourg postal service from accepting subscriptions to the Journal d'Arlon. This was futile as it was enough for the city's residents to leave the gates to subscribe at the Belgian post office established in Eich.[8]

Diplomatic tensions and London Conference

For a few years, Luxembourg became a focal point of international tensions in Europe. The Grand Duke requested immediate assistance from the Diet of the German Confederation on 15 October 1830 to suppress pro-Belgian disturbances in Luxembourg. While the Confederation was obliged to intervene due to the obligations of the Final Act of the Vienna Congress, the intervention was politically inconvenient because it risked France siding with Belgium, leading to a European war. The Confederation — eager to contain the conflict — employed procedural means and delayed the decision until 17 November, when it concluded that Luxembourg, being part of the Confederation, could not be included in the arrangement the powers were considering for Belgium. To appease tensions, France communicated to Brussels on 20 November that none of the five powers considered the Confederation's intervention as foreign interference. On 20 January 1831, the London Conference decided regarding the delineation of borders between the Netherlands and Belgium that Luxembourg would remain independent of Belgium, part of the German Confederation.[4]

Taking advantage of this preliminary decision, the King of the Netherlands quickly established a separate administration in Luxembourg. In February, he appointed Duke Bernard of Saxe-Weimar as the governor-general for Luxembourg. He then set up a government commission in the capital, which exercised power only over the territory effectively controlled by the Confederation. This commission, established by William I to salvage what could be saved, and staffed with foreigners, could generously be considered the first Luxembourgish executive. The measure emphasised a de facto division, preceding the legal separation from Belgium by about a decade.[4]

Faced with France's armament, on 17 March 1831, the Diet decided to reinforce the garrison in Luxembourg but, to avoid provoking French public opinion, enlisted troops from Waldeck, Lippe, and Schaumburg-Lippe. Undisciplined and poorly commanded, these troops rebelled, expressing their sympathy for the Belgian cause. In November 1831, they were repatriated and replaced by reserve Prussian units stationed in the Trier region.[4]

Meanwhile, on 18 March 1831, the King once again insisted on finally obtaining the Confederation's assistance. The Confederation again evaded the decision by deciding to set up an intervention force, but postponing the decision on whether to actually intervene. In the end, there was no intervention. On 30 August 1831, the London Conference proposed settling the issue through territorial partition, which occurred through the Treaty of 15 October 1831. The western part of the Grand Duchy, including Arlon, Bastogne, and Bouillon, would go to Belgium. The eastern part, under the sovereignty of the Grand Duke, would remain a member state of the German Confederation. The Grand Duke would be territorially compensated for the loss of the Walloon part of Luxembourg by receiving territory from the Limburg province located on both sides of the Meuse. This solution would secure necessary communications with the fortress of Maastricht, but it did not compensate for the loss in terms of territory or population. The division allowed the Grand Duke to choose whether to join Limburg to the Netherlands or to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. While Belgium accepted this arrangement, the Dutch delayed their response until 15 November 1833, when they expressed agreement with the partition but reserved the Limburg question.

1839 resolution: separation of Luxembourg and Belgium

1, 2 and 3 United Kingdom of the Netherlands (until 1830)

1 and 2 Kingdom of the Netherlands (after 1839)

2 Duchy of Limburg (1839–1867) (in the German Confederacy after 1839 as compensation for Walloon Luxemburg)

3 and 4 Kingdom of Belgium (after 1839)

4 and 5 Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (borders until 1839)

4 Province of Luxembourg (Walloon Luxemburg, to Belgium in 1839)

5 Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (German Luxemburg; borders after 1839)

In blue, the borders of the German Confederation.

In blue, the borders of the German Confederation.This issue remained unresolved until 15 June 1838, when the Grand Duke agreed to provide territorial compensation to the Confederation. On 5 September 1839, the Grand Duke declared that the newly-formed Duchy of Limburg would join the Confederation, with a population of 145,527.[4]

By the same decision on 5 September 1839, the Diet admitted the Duchy of Limburg to the Confederation, transferring the rights and obligations of the pre-separation Grand Duchy collectively to the diminished Grand Duchy and Limburg. Henceforth, the international status of these two territories was as follows: Luxembourg was an independent state, linked to the Netherlands by a personal union; whereas Limburg was simply a province of the Netherlands. Despite this difference, the two territories, living under different constitutional regimes, were considered a single member of the Confederation, with the singular voice expressed by the diplomatic representative of the King of the Netherlands and Grand Duke of Luxembourg.[4]

Aftermath

Belgian reaction and annexationism

The separation between Belgium and present-day Luxembourg was felt with trepidation by the Belgian people. Belgian annexationism, which would manifest sporadically from 1840 to 1919, i.e., for nearly 80 years, and would evoke sympathy or defense reactions in Luxembourg, initially had a comprehensible origin.[4]

Luxembourg as buffer state

The history of the country during the decade from 1830 to 1840 shows that Luxembourg, created by the powers as a distinct state because of its fortress, was maintained by these powers for the same reason. It also illustrates the importance of the military problem—the Allied barrier against France—in the genesis of Luxembourg in 1815 and its preservation in 1839. Indeed, the essential reason for its creation in 1815, the membership in the German Confederation, and the federal nature of the fortress were decisive factors in the state's maintenance, imposed on the Luxembourgers by the European powers.[4]

Germanisation policy of William I

The path of integrating the country into Belgium was closed by the great powers due to the Treaties of London on 15 November 1831, and 19 April 1839. As a result, Luxembourg's two political forces — the progressive liberals and the Orangist conservatives — continued to diverge in their objectives: liberals focused on the constitutional regime to be given to the country, while the Orangists, for whom independence had been a sign of borrowed patriotism, supported William I's policy of Germanisation. In doing so, both questioned the identity and future of the country. The nine years during which Luxembourg's population was caught between two fronts, which would have liked to join the rebel camp, had a significant consequence, as the country would leave the Dutch sphere of influence and enter that of the Confederation and the powerful hegemonic neighbour that was Prussia.[4]

This policy of Germanisation manifested itself on the ground by sending a few German officials—people from Nassau and Hesse—to Luxembourg for high administration and adopting the German language as the administrative language. These two measures obviously aimed to deepen the separation between Luxembourg and Belgium but were added to the Germanisation factors inherent in the constitutional problem and the crucial issue of the country's economic ties with its neighbors; enclosed by customs duties, the country risked suffocation.[4]

French annexationism

The question of Belgium's survival, and consequently the chances of Luxembourg's survival, had been raised in the London negotiations. The French had pushed for them to be divided up, with Prussia receiving Limburg, Liège, and Luxembourg; France getting Namur, Hainaut, and West Flanders; and the rest going to the Netherlands. These ideas of division were linked to the Allies' negotiations in 1814 and 1815, but they would be revisited in 1866 in the talks between Count Benedetti and Otto von Bismarck over the annexation of Belgium and Luxembourg.[4]

Commemoration and celebration

The events of 1839 were seen negatively by many in Luxembourg at the time. Over the course of the years, however, it came to be treated by historians and political leaders as a defining moment for the country's independence. The centenary was celebrated in 1939, in a time of increasing international tensions and when the country's existence seemed threatened by Nazi Germany. The 150-year anniversary was celebrated in 1989.

See also

References

Bibliography and further reading

- Bauler-Margue, Andrée (1 January 1983). "Le clergé luxembourgeois de 1815 à 1839 fut-il orangiste?". Hémecht (in French). 35 (1): 53ff.

- Bour, Jos. (2 October 1980). "L'Église luxembourgeoise et la Révolution belge (1830-1831)". Luxemburger Wort (in French).

- Calmes, Christian (1 October 1969). "Malaise et annexionisme belge en 1867". Hémecht (in French). 21 (4): 373ff.

- Calmes, Christian (14 April 1989). "Le Luxembourg sous le double régime belge et hollandais 1830-1839". d'Letzeburger Land (in French). p. 9.

- Feltes, Paul (1 January 1998). "L'organisation judiciaire du Luxembourg au 19ᵉ siècle: un élément de la formation d'un état et d'une administration (1839-1885)". Hémecht (in French). 50 (1/2): 27–68, 135–176.

- Grosbusch, André (1 October 2000). "La liberté de la presse au Luxembourg". Hémecht (in French). 52 (4): 453ff.

- Holzberger, Hiltrud (1 October 1994). "Cholera und politische Verfolgung: Das verloren geglaubte Tagebuch des Mathias Wellenstein". Hémecht (in German). 46 (4): 699ff.

- Hoscheit, Jean-Marc (1 April 1992). "La coopération diplomatique entre les Pays-Bas et le Grand-Duché de Luxembourg de 1841 à nos jours". Hémecht (in French). 44 (2): 201ff.

- Neu, Peter (1 October 2003). "Die belgische Revolution von 1830 und ihre Ausstrahlung auf den luxemburgisch-deutschen Grenzraum". Hémecht (in German). 55 (4): 525ff.

- Pescatore, Pierre (1 April 1967). "La souveraineté nationale et les traités internationaux: au fil de l'histoire luxembourgeoise (1815-1956)". Hémecht (in French). 19 (2): 129ff.