List of works by Gloria E. Anzaldúa

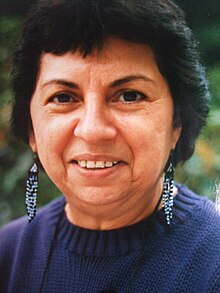

Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa (1942–2004) was a prolific Chicana writer of prose, fiction, and poetry.[1] After moving from her native Texas to California in 1977, she exclusively focused on her writing,[2] publishing dozens of pieces of writing before her death.[3] She left behind several manuscripts in progress when she died.[3]

Among her most popular pieces of writing are This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981) and Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987; especially a section entitled "La conciencia de la mestiza/Towards a Mestiza Consciousness").[4] She wrote variously about feminism, the role of women of color in feminism, self-reflection, borderlands (particularly the space around the Mexico–United States border), Indigenous mythology and culture, and identity and contradiction.[5][6] She developed the framework of mestiza consciousness, contributed to the field of queer theory, and valued intersectionality over single-identity movements.[7] She is remembered as an especially influential writer in late nineteenth century cultural studies.[8]

Books

| Title | Year | Publisher | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This Bridge Called My Back: Writings By Radical Women of Color | 1981 | Persephone Press | Edited collection with Cherríe Moraga | [9] |

| Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza | 1987 | Aunt Lute Books | A text that exists within several genres | [10][8] |

| Making Face, Making Soul / Hacienda Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Women of Color | 1990 | Aunt Lute Books | Edited collection | [10] |

| Interviews/Entrellistas | 2000 | Routledge | Edited by AnaLouise Keating | [10] |

| this bridge we call home: radical visions for transformation | 2002 | Routledge | Edited with AnaLouise Keating | [10] |

| Light in the Dark / Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality | 2015 | Duke University Press | Published after her death | [11] |

| La Serpiente Que Se Come Su Cola: The Death and Rebirth Rites-of-Passage of a Chicana Lesbian | — | — | Never published | [12] |

| La Prieta | — | — | Never published, intended to be a "novel/collection of stories" | [13] |

Articles and essays

| Title | Year | Publication | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Speaking in Tongues: A Letter to Third World Women Writers" | 1981 | This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color | Written in the epistolary format | [14] |

| "La Prieta" | 1981 | Anzaldúa began writing this essay in 1979 and finished it in 1981. An autohistoria | [15] | |

| "En Rapport, In Opposition: Cobrando cuentas a las nuestras" | 1987 | Sinister Wisdom | — | [16] |

| "Bridge, Drawbridge, Sandbar, or Island: Lesbians-of-Color Hacienda Alianzas" | 1990 | Bridges of Power: Women's Multicultural Alliances | A longer version of a 1988 speech | [17] |

| "Metaphors in the Tradition of the Shaman" | 1990 | Conversant Essays: Contemporary Poets on Poetry | — | [18] |

| "To(o) Queer the Writer – Loca, escritora y chicana" | 1991 | Inversions: Writing by Dykes, Queers, and Lesbians | An edited transcript | [19] |

| "Border Arte: Nepantla, el Lugar de la Frontera" | 1993 | La Frontera/The Border: Art about the Mexico/United States Border Experience | Discussion of Coyolxauhqui, autohistoria, nepantla, and the visual arts | [20] |

| "Foreword" | 1996 | Cassell's Encyclopedia of Queer Myth, Symbol and Spirit | Discusses spirituality. Worked on a longer version until her death | [21] |

| "Let us be the healing of the wound: The Coyolxauhqui imperative – la sombra y el sueño" | 2005 | One Wound for Another / Una Herida por otra: Testimonios de Latin@s in the U.S. through Cyberspace (11 de septiembre de 2001 – 11 de marzo de 2002) | Final essay published before her death, about post-September 11th policy and nepantla | [22] |

| "Born Under the Sign of the Flower: Los jotos in Ancient Mexico and Modern Aztlán" | — | — | Unpublished essay, written in the 1980s about the HIV/AIDS pandemic | [23] |

| "S.I.C.: Spiritual Identity Crisis" | — | — | Unpublished essay, written before 1999 about her diabetes diagnosis | [24] |

| "Spiritual Activism: Making Altares, Making Connections" | — | — | Unpublished essay, written before 1999 about the HIV/AIDS pandemic | [25] |

Fiction

| Title | Year | Publication | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "El Paisano is a Bird of Good Omen" | 1982/1983 | Conditions and Cuentos: Stories by Latinas | Began writing in 1974 as "La Boda" and conceptualized in the early 1980s as a sequence in a novel. Prietita story | [26][27][28] |

| "People Should Not Die in June in South Texas" | 1985/1993 | My Story's On: Ordinary Women, Extraordinary Lives and Growing Up Latino: Reflections on Life in the United States | Prietita story | [29][30][18] |

| "La historia de una marimacha" | 1989 | Third Woman Press | — | [18] |

| "Life Line" | 1989 | Lesbian Love Stories, vol. 1 | — | [18] |

| "She Ate Horses" | 1990 | Lesbian Philosophies and Cultures | — | [18] |

| "Ms. Right, My True Love, My Soul Mate" | 1991 | Lesbian Love Stories, vol. 2 | — | [18] |

| "Ghost Trap / Trampa de espanto" | 1992 | New Chicana/Chicano Writing | First written in 1990. Included in La Prieta. Humorous story | [13] |

| "Puddles" | 1992 | Published in 1992, revised until at least 1998. Some of the revisions were substantial, including changing the point of view and the title (to "Velada de una lagartija") | [31][18] | |

| "Swallowing Fireflies / Tragando Luciérnagas" | 2003 | Telling Moments: Autobiographical Lesbian Short Stories | — | [18] |

All of her children's books,[32] and many of her short stories for children, feature Prieta/Prietita[A] as the main character.[34] Most of the Prietita stories remain unpublished,[26] as do many stories about childhood or written for children.[33] She wrote for stories for Mexican-American children to challenge the feelings of inferiority they learned in school as a project of "decolonizing, disindoctrinating ourselves from the oppressive messages we have been given".[35]

| Title | Year | Publisher | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friends from the Other Side / Amigos del Otro Lado | 1993 | Children's Book Press | Illustrated, bilingual | [36][37][38] |

| Prietita and the Ghost Woman / Prietita y la Llorona | 1995 | Inverts the traditional reading of la Llorona as fearful | [39][40] |

Poems

Anzaldúa included poems in her other writing, including her book Borderlands / La Frontera.[41] Scholar Ariana Vigil characterizes the poetry of Anzaldúa as a site of "necessary social critique", drawing upon her experiences that are "linked to a raced, working-class condition and subject".[42]

| Title | Year | Publication | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Tihueque" | 1976 | Tejidos | Her first publication. Tihueque is Nahuatl for "now let us go". | [43] |

| "To Delia, Who Failed on Principles" | 2009 | The Gloria E. Anzaldúa Reader | Written in 1974, published posthumously | [44] |

| "Reincarnation" | [45] | |||

| "I Want to be Shocked Shitless" | [46] | |||

| "The Occupant" | Written around 1975, performed often in the 1980s; published posthumously | [47] | ||

| "The New Speaker" | Written in the 1970s, published posthumously | [48] | ||

| "The coming of el mundo surdo" | Written in 1977. Surdo is usually spelled zurdo, but Anzaldúa altered the spelling; published posthumously | [49] | ||

| "Enemy of the State" | Included in the 1985 version of Borderlands / La Frontera but not the published version; published posthumously | [50] | ||

| "Del Otro Lado" | [51] | |||

| "Encountering the Medusa" | [52] | |||

| "The Presence" | Written between 1984 and 1990, published posthumously | [53] | ||

| "La vulva es una herida abierta / The vulva is an open wound" | Written around 1990, published posthumously. Autobiographical poem | [54] | ||

| "Yemayá" | Written before 1991, published posthumously. Discusses the Yoruban goddess Yemayá | [55] | ||

| "How to" | Written and revised until 1997, published posthumously | [56] | ||

| "Healing Wounds" | Written and revised until 2002, published posthumously | [57] | ||

| "Like a spider in her web" | [58] | |||

| "The Postmodern Llorona" | Written and revised until 2003, published posthumously | [59] | ||

| "Llorona Coyolxauhqui" | Written and revised until 2003, published posthumously. Discusses la Llorona, Coyolxauhqui, nepantla, and el cenote | [60] | ||

| "When I write I hover" | Prose poem, published posthumously | [61] |

Notes and references

Notes

Citations

- ^ Keating 2009, pp. 1, 4, 325, 335.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 4.

- ^ a b Keating 2009, pp. 4, 6.

- ^ Keating 2009, pp. 5, 8.

- ^ Keating 2009, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Perez 2022, p. 160.

- ^ Keating 2009, pp. 5, 10.

- ^ a b Perez 2022, p. 154.

- ^ Keating 2009, pp. 72, 337.

- ^ a b c d Keating 2009, p. 337.

- ^ Gutierrez-Perez 2017, p. 306.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 70.

- ^ a b Keating 2009, p. 157.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 38.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 111.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 140.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Keating 2009, p. 338.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 163.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 176.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 229.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 303.

- ^ Hey-Colon 2022, p. 39.

- ^ Hey-Colon 2022, p. 25.

- ^ Hey-Colon 2022, p. 32.

- ^ a b Keating 2005, p. 11.

- ^ Woodward 1989, p. 530.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 51.

- ^ Blanchard 2005, p. 35.

- ^ Keating 2005, pp. 11, 256.

- ^ Hey-Colon 2022, pp. 17, 22, 37.

- ^ Vásquez 2005, p. 64.

- ^ a b Millán 2015, p. 204.

- ^ Blanchard 2005, p. 34.

- ^ Rebolledo 2006, p. 283.

- ^ Lunsford 1998, p. 2.

- ^ Millán 2015, p. 207.

- ^ Rebolledo 2006, pp. 279, 284.

- ^ Rebolledo 2006, pp. 279, 283–284.

- ^ Vásquez 2005, p. 66.

- ^ Vigil 2016, p. 86.

- ^ Vigil 2016, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 19.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 21.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 36.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 97.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 99.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 101.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 119.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 198.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 242.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 232.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 249.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 276.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 280.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 295.

- ^ Keating 2009, p. 238.

Works cited

- Gutierrez-Perez, Robert (2017). "Anzaldúa, Gloria E. Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality". Women's Studies in Communication. 40 (3): 306–308. doi:10.1080/07491409.2017.1334446. S2CID 149070380.

- Keating, AnaLouise, ed. (2005). EntreMundos/AmongWorlds: New perspectives on Gloria E. Anzaldúa. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403977137.

- Blanchard, Mary Loving. "Reclaiming pleasure: Reading the body in 'People Should Not Die in June in South Texas'". In Keating (2005).

- Vásquez, Edith M. "La gloriosa travesura de la musa que cruza / the misbehaving glory(a) of the border-crossing muse: Transgression in Anzaldúa's children's stories". In Keating (2005).

- Hey-Colon, Rebeca L. (2022). "Chronic illness and transformation in Gloria Anzaldúa's "Puddles"". Aztlán. 47 (1): 15–42.

- Keating, AnaLouise, ed. (2009). The Gloria E. Anzaldúa reader. Duke University Press.

- Lunsford, Andrea A. (1998). "Toward a mestiza rhetoric: Gloria Anzaldúa on composition and postcoloniality". JAC. 18 (1): 1–27. JSTOR 20866168.

- Millán, Isabel (2015). "Contested children's literature: Que(e)ries into Chicana and Central American autofantasías". Signs. 41 (1): 199–244. doi:10.1086/681919. hdl:2097/32551. JSTOR 10.1086/681919. S2CID 147670637.

- Perez, Domino Renee (2022). Fatherhood in the borderlands: A daughter's slow approach. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9781477326350.

- Rebolledo, Tey Diana (2006). "Prietita y el otro lado: Gloria Anzaldúa's literature for children". PMLA. 121 (1): 279–284. JSTOR 25486306.

- Vigil, Ariana (2016). "Heterosexualization and the state: The poetry of Gloria Anzaldúa". Chicana/Latina Studies. 16 (1): 86–109. JSTOR 45186447.

- Woodward, Carolyn (1989). "Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza by Gloria Anzaldúa". NWSA Journal. 1 (3): 530–532. JSTOR 4315935.