Metagonimiasis

| Metagonimiasis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Metagonimus yokogawai infection[1] | |

| |

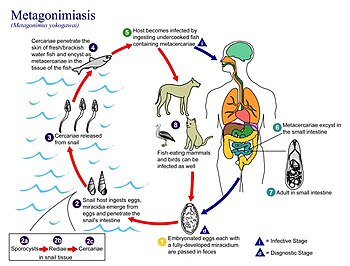

| Life cycle of Metagonimus yokogawai. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Asymptomatic but can have abdominal pain, diarrhea[2] |

| Causes | Metagonimus yokogawai[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Finding of characteristic small operculated eggs in feces (stool sample)[3] |

| Prevention | Discourage ingestion of raw, undercooked fish[3] |

| Treatment | Praziquantel[3] |

Metagonimiasis (or Metagonimus yokogawai infection[1])is a disease caused by an intestinal trematode, most commonly Metagonimus yokagawai, but sometimes by M. takashii or M. miyatai. The metagonimiasis-causing flukes are one of two minute flukes called the heterophyids.The incubation period is around 14 days .[4][2]

Metagonimiasis was described by Katsurasa in 1911–1913 when he first observed eggs of M. yokagawai in feces. M. takahashii was described later first by Suzuki in 1930 and then M. miyatai was described in 1984 by Saito.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The main symptoms are diarrhea and abdominal pain. Because symptoms are often mild, infections can often be easily overlooked but diagnosis is important. Flukes attach to the wall of the small intestine, but are often asymptomatic unless in large numbers. Infection can occur from eating a single infected fish source. Peripheral eosinophilia is associated especially in early phase. When present in large numbers, can cause chronic intermittent diarrhea, nausea, and vague abdominal pains. Clinical complaints can also include lethargy and anorexia. In acute metagonimiasis, clinical manifestations are developed only a week after infection.[5][3][6]

Complications

Occasionally, flukes invade the mucosa and eggs deposited in tissue may gain access to circulation; this may lead to eggs embolizing in the brain, spinal cord, or heart.An interesting case in Japan found diabetes mellitus (DM) to be a sign of chronic infection with intracerebral hemorrhages as the acute sign of aggravation.Two months after administering praziquantel, the hemorrhages were gone, as was the diabetes. This unique case shows the potential of additional symptoms associated with metagonimiasis that are still unknown.[3][7][1]

Cause

Metagonimiasis is most commonly caused by one of the two smallest flukes known to infect man, Metagonimus yokagawai. More rarely, metagonimiasis can arise from infection with M. takahashii or M. miyatai. Recent studies analyzing the DNA of the three agents causing metagonimiasis found that DNA sequencing supports M. yokagawai and M. takahashii be placed in the same clade, and phylogenic tree analysis supports their genetic similarity. M. miyatai, however, was found to be more genetically distinct, and it was concluded it should be nominated as a separate species. .Trematodes are one class of phylum Platyhelminthes from the order Digenia and are generally referred to as flukes. Metagonimiasis is of the family Herterophyidae.[8][9][10][11]

Transmission

Transmission requires two intermediate hosts, the first of which is snails, most commonly of species Semisucospira libertina, Semiculcospira coreana, and Thiara granifera.Infection is acquired through the secondary intermediate host, fish, that have not been thoroughly cooked.Many common fish species can be infected including Carassius auratus, Cyprinus carpio, Zacco temminckii, Protimus steindachneri, Acheilognathus lancedata, and Pseudorashora parva[12][5][13][14]

Definitive hosts include humans and various fish-eating mammals, primarily dogs, cats, and pigs. Fish-eating birds may also be infected with metagonimiasis.[5]

Reservoirs

Reservoirs include fish-eating mammals such as dogs, cats as well as fish-eating birds. The presence of heterophyid infection in humans is generally caused by a lack of host specificity by the parasites, as seen in the many non-human reservoirs for metagonimiasis.[15][5]

Morphology

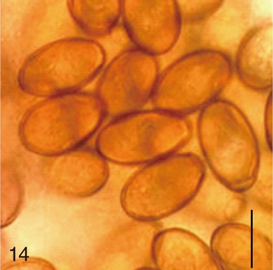

-

Metagonimus miyatai eggs

-

Morphology -a) Metagonimus yokogawai, b) Metagonimus takahashii, and c) Metagonimus miyatai.

-

Adult Fluke (from CDC)

Eggs

The morphology of the eggs is very important for diagnosis, but is difficult as eggs are very small. Eggs have a smooth, hard shell that is transparent and yellow-brown with a more conventional, ovoid egg shape. They are about the same size as those of Heterophyes and Clonorchis, usually measuring 26-28 μm length and 15-17μm width. The egg also has a very slight opercular shoulder, marking the line of cleavage between the shell and operculum, an "escape hatch" for the mircidium. The Clonorchis has more distinctive tapering and a seated operculum that help distinguish it more readily from Metagonimus species.[16]

Adult flukes

The body of the adult disease-causing agent of metagonimiasis is often described as leaf-shaped, similar to most trematodes. It is one of the smallest intestinal flukes, and is only slightly larger than Heteropheres. The most prominent feature is that its ventral sucker is deflected to the right of its midline and is closely associated with the opening of the genital pore. The testes are large and diagonal to each other while the smaller ovary is anterior to the testes and the uterus is filled with eggs. The uterus winds forward to the genital pore and is the largest organ in the body.M. yokogawai adult flukes are 1 to 2 mm long and 0.4 to 0.6 mm wide .[17][5]

Diagnosis

Metagonimiasis is diagnosed by eggs seen in feces. Only after antihelminthic treatment will adult worms be seen in the feces, and then can be used as part of a diagnostic procedure. A study of the efficacy of ELISA tests to diagnose metagonimiasis implied that simultaneous screening of specific antibodies to several parasite agents are important in serological diagnosis of acute parasitic disease and more research should be done on the efficacy of these methods of diagnosis.[18][16][19]

Diagnosis may be difficult because the egg-laying capacity of heterophyids is limited, and therefore sedimentation concentration procedures may be needed to demonstrate eggs in lighter infections. Accurate species identification is also difficult because eggs of most flukes are similar in size and morphology, especially those of Heterophyes heterophyes, Clonorchis and Opisthorchis. It is important to ask where the person may have contracted the disease, find out if they have been to an endemic area.[20][18]

Prevention

Several public health prevention strategies could help lower the rates of metagonimiasis. One is to control the intermediate host (snails). This can be done through use of molluscidals. Another is to use education to ensure all people, especially in areas were the disease regularly occurs, fully cook all fish. This could potentially be problematic and not as effective as hoped as many of the people affected by metagonimiasis eat raw or pickled fish as part of a traditional, long-seated dietary practice. Additionally, implementing more sanitary water conditions would reduce the continual reintroduction of eggs to water sources, thus restarting the lifecycle. Complete control of metagonimiasis presents several potential problems because it does have several reservoir hosts, thus eradication is unlikely.[21][22][16]

Treatment

Praziquantel is recommended in both adult and pediatric cases with dosages of 75 mg/kg/d in 3 doses for 1 day. Praziquantel is a Praziniozoquinoline derivative that alters the calcium flux through the parasite tectum and causes muscular paralysis and detachment of the fluke. Prizaquantel should be taken with liquids during a meal and as provided commercially as Biltricide. Praziquantel is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of metagonimiasis, but is approved for use on other parasitic infections.[16][23][3]

Praziquantel has some side effects but they are generally relatively mild and transient and a review of evidence shows it overall a well-tolerated drug. Possible side effects include abdominal pain, allergy, diarrhea, headache, nausea or vomiting, exacerbation of porphyries, pruritus, rash, or dizziness. In fact, in 2002, the World Health Organization recommended the use of Praziquantel in pregnant and lactating women.[24][25][26]

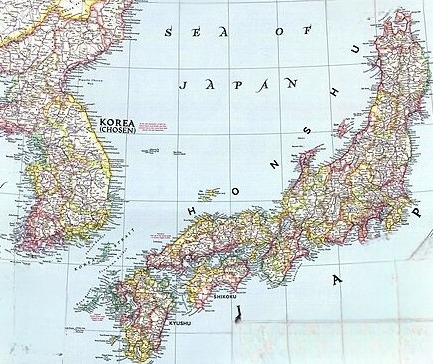

Epidemiology

Metagonimiasis infections are endemic or potentially endemic in 19 countries including Japan, Korea, China, Taiwan, the Balkans, Spain, Indonesia, the Philippines and Russia. Human infections outside endemic areas may result from ingesting pickled fish or sushi made from fish imported from endemic areas.[27][21]

Korea

Food-borne trematodes are currently the most important parasitic infections in Korea and approximately 240,000 Koreans are believed to be currently infected. M. yokagawai infections are found mostly around the large and small streams where sweetfish live and have been identified as endemic foci. M. miyatai and M. takahashii are prevalent along the upper reaches of the big rivers where minnows and carps are caught for eating raw.[28][29][6]

Japan

Metagonimiasis is also common in Japan, with 10-15% prevalence rates in populations bordering major rivers and 150,000 estimated infected. Food-borne trematodes are most common in rural areas where traditional food habits are more preserved and raw freshwater fishes are incorporated into the diet. Metagonimiasis has become an infection of higher social classes in Hong Kong and Japan, owing to its frequent consumption of raw fish.[30][6][31]

India

There have also recently been two reported cases in India, a location in which occurrence of infection is almost unknown. The second case, in 2005, was in a 6-year-old female patient presenting with loose watery stools for four days. Upon examination, M. yokagawai eggs were found in stool, but the patient left and further analysis and treatment could not be completed.[14][32]

See also

Notes

- 1.^ This is a case report which merits inclussion

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Infection by Metagonimus yokogawai (Concept Id: C0025530) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 10 September 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Metagonimiasis - About the Disease - Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Long, Sarah S.; Pickering, Larry K.; Prober, Charles G. (2008). Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Saunders. pp. 1332–1334. ISBN 978-0-7020-3468-8.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Shimazu, T; Kino, H (October 2015). "Metagonimus yokogawai (Trematoda: Heterophyidae): From Discovery to Designation of a Neotype". The Korean journal of parasitology. 53 (5): 627–39. doi:10.3347/kjp.2015.53.5.627. PMID 26537043. Archived from the original on 2024-04-24. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "CDC - DPDx - Metagonimiasis". www.cdc.gov. 21 January 2019. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Chai, J-Y (2014). "Helminth-Trematode: Metagonimus yokogawai". Encyclopedia of Food Safety. Elsevier. p. 164–169. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-378612-8.00157-8. ISBN 978-0-12-378613-5.

- ↑ Yamada, Shoko Merrit; Yamada, Shokei; Takada, Hitomi; Hoshiai, Yayoi Carol; Yamada, Shotetsu (February 2008). "Case of metagonimiasis complicated with multiple intracerebral hemorrhages and diabetes mellitus". Journal of Nippon Medical School = Nippon Ika Daigaku Zasshi. 75 (1): 32–35. doi:10.1272/jnms.75.32. ISSN 1345-4676. Archived from the original on 2024-05-13. Retrieved 2024-05-11.

- ↑ The biology of echinostomes: from the molecule to the community. New York, NY: Springer. 2009. pp. 147–183. ISBN 978-0-387-09576-9. Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Food Safety. Academic Press. 12 December 2013. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-12-378613-5. Archived from the original on 27 April 2024. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ↑ "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Metagonimus yokogawai (Katsurada, 1912) Katsurada, 1912". www.marinespecies.org. Archived from the original on 2024-04-07. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ↑ Lee, Soo-Ung; Huh, Sun; Sohn, Woon-Mok; Chai, Jong-Yil (September 2004). "Sequence comparisons of 28S ribosomal DNA and mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I of Metagonimus yokogawai, M. takahashii and M. miyatai". The Korean Journal of Parasitology. 42 (3): 129–135. doi:10.3347/kjp.2004.42.3.129. ISSN 0023-4001. Archived from the original on 2024-05-13. Retrieved 2024-05-13.

- ↑ Chai, Jong-Yil; Lee, Soon-Hyung (June 2002). "Food-borne intestinal trematode infections in the Republic of Korea". Parasitology International. 51 (2): 129–154. doi:10.1016/S1383-5769(02)00008-9. Archived from the original on 2024-04-11. Retrieved 2024-04-24.

- ↑ Chai, JY; Jung, BK (September 2017). "Fishborne zoonotic heterophyid infections: An update". Food and waterborne parasitology. 8–9: 33–63. doi:10.1016/j.fawpar.2017.09.001. PMID 32095640. Archived from the original on 2024-05-13. Retrieved 2024-05-13.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Parija, Subhash Chandra; Chaudhury, Abhijit (24 September 2022). Textbook of Parasitic Zoonoses. Springer Nature. pp. 309–313. ISBN 978-981-16-7204-0. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ↑ Chai, Jong-Yil (2017). "Metagonimus". Laboratory Models for Foodborne Infections. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-315-12008-9. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Mahanta, Jagadish (2022). "Metagonimiasis". Textbook of Parasitic Zoonoses. Springer Nature. pp. 309–316. ISBN 978-981-16-7204-0. Archived from the original on 2023-09-10. Retrieved 2024-04-21.

- ↑ Chai, Jong-Yil; Darwin Murrell, K.; Lymbery, Alan J. (October 2005). "Fish-borne parasitic zoonoses: Status and issues". International Journal for Parasitology. 35 (11–12): 1233–1254. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.013. Archived from the original on 14 April 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Cong, W; Elsheikha, HM (June 2021). "Biology, Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Selected Fish-borne Parasitic Zoonoses". The Yale journal of biology and medicine. 94 (2): 297–309. PMID 34211350. Archived from the original on 2024-04-18. Retrieved 2024-04-28.

- ↑ Toledo, Rafael; Alvárez-Izquierdo, Maria; Muñoz-Antoli, Carla; Esteban, J. Guillermo (2019). "Intestinal Trematode Infections". Digenetic Trematodes. Springer International Publishing. pp. 181–213. ISBN 978-3-030-18615-9. Archived from the original on 2023-05-28. Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- ↑ "Heterophyiasis and Related Trematode Infections - Infectious Diseases". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 1 April 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Vaishnavi, Chetana (31 March 2013). Infections of the Gastrointestinal System. JP Medical Ltd. p. 434. ISBN 978-93-5090-352-0. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ↑ "Integrated guide to: Sanitary Parasitology" (PDF). WHO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2024. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ↑ Fukushige, Mizuho; Chase-Topping, Margo; Woolhouse, Mark E. J.; Mutapi, Francisca (17 March 2021). "Efficacy of praziquantel has been maintained over four decades (from 1977 to 2018): A systematic review and meta-analysis of factors influence its efficacy". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 15 (3): e0009189. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009189. ISSN 1935-2735. Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ↑ "Praziquantel". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2012. Archived from the original on 7 March 2024. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ↑ "Praziquantel: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 5 July 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ↑ "Report of the WHO informal consultation on the use of praziquantel during pregnancy/lactation and albendazole/mebendazole in children under 24 months: Geneva, 8−9 April 2002". fctc.who.int. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ↑ Lee, GS; Cho, IS; Lee, YH; Noh, HJ; Shin, DW; Lee, SG; Lee, TY (March 2002). "Epidemiological study of clonorchiasis and metagonimiasis along the Geum-gang (River) in Okcheon-gun (county), Korea". The Korean journal of parasitology. 40 (1): 9–16. doi:10.3347/kjp.2002.40.1.9. PMID 11949215. Archived from the original on 2024-04-16. Retrieved 2024-04-23.

- ↑ Cho, S. Y.; Kang, S. Y.; Lee, J. B. (1984). "Metagonimiasis in Korea". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 34 (9B): 1211–1213. ISSN 0004-4172. Archived from the original on 2024-04-30. Retrieved 2024-04-28.

- ↑ Berman, Jules J. (31 August 2012). Taxonomic Guide to Infectious Diseases: Understanding the Biologic Classes of Pathogenic Organisms. Academic Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-12-415913-6. Archived from the original on 6 May 2024. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ↑ Pornruseetairatn, Siritavee; Kino, Hideto; Shimazu, Takeshi; Nawa, Yukifumi; Scholz, Tomáš; Ruangsittichai, Jiraporn; Saralamba, Naowarat Tanomsing; Thaenkham, Urusa (1 March 2016). "A molecular phylogeny of Asian species of the genus Metagonimus (Digenea)—small intestinal flukes—based on representative Japanese populations". Parasitology Research. 115 (3): 1123–1130. doi:10.1007/s00436-015-4843-y. ISSN 1432-1955. Archived from the original on 10 June 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ↑ "Review on the Epidemiological Profile of Helminthiases and their Control in the Western Pacific Region, 1997-2008". WHO. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ↑ Uppal, B; Wadhwa, V (January 2005). "RARE CASE OF METAGONIMUS YOKOGAWAI". Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 23 (1): 61–62. doi:10.1016/S0255-0857(21)02717-1. Archived from the original on 18 April 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

Further reading

- Ahn, Yung-Kyum. "Intestinal flukes of genus Metagonimus and their second intermediate hosts in Kangwon-do." Korean Journal of Parasitology. Vol. 31: 331–340. 1993.

- Ash, Lawrence; Orihel, Thomas. Atlas of Human Parasitology. Fourth Edition. American Society of Clinical Pathologists. 1997.

- Chai, Jong-Yil et al. "An epidemiological study of metagonimiasis along the upper reaches of the Namham River." Korean Journal of Parasitology. Vol. 31: 99–108. 1993.

- Despommier D.; Gwadz R.; Hotez P.; Knirsch C. Parasitic Diseases. Fifth Edition. New York: Apple Trees Productions. 2006.

- FAO/NACA/WHO. "Food Safety Issues Associated with Products from Aquaculture." WHO Technical Report Series. Geneva, 1999.

- Han, In-Soo et al. "An Epidemiologic Study on Clonorchiasis and Metagonimiasis in Riverside Areas in Korea." Korean Journal of Parasitology. Vol. 19: 137–150. 1981.

- Lee, Jin-Ju, et al. "Decrease of Metagonimus yokogawai Endemicity along the Tamjin River Basin." Korean Journal of Parasitology. Vol. 46: 269–291. 2008.

- Lee, Gye-Sung et al. "Epidemiological study of clonorchiasis and metagonimiasis along the Geum-gang in Okcheon-gun, Korea." Korean Journal of Parasitology. Vol. 40: 9–16. 2002.

- Lee, Seoung Cheol et al. "Antigenti c protein fractions of Metagonimus yokogawai reacting with patient sera." Korean Journal of Parasitology. Vol. 31: 43–48. 1993.

- Lee, Soo-ung et al. "A cytogenetic study on human intestinal trematodes of the genus Metagonimus in Korea." Korean Journal of Parasitology. Vol. 37: 237–241. 1999.

- Markell, EK; John, DT; Krotoski, WA. Markell and Voge's Medical Parasitology. Ninth Edition. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company. 2006.

- Mehlhorn, Heinz. Encyclopedic Reference of Parasitology. Second Edition. Germany: Springer. 2001.

- Pawlowski, Zbigniew S. "Intestinal Helminthiases and Human Health: Recent Advances and Future Needs." Parasitic Disease Programme, WHO. 1987.

- Rim, Han-Jong et al. "Antihelminthic Effects of Various Drugs against Metagonimiasis." Korean Journal of Parasitology. Vol. 16: 117–122. 1978.

- Rim, Han-Jong. "Classification and host specificity of Metagonimus spp. from Korean freshwater fish." Korean Journal of Parasitology. Vol. 34: 7-14. 1996.

- Shin, Eun-Hee et al. "Trends in parasitic diseases in the Republic of Korea." Trends in Parasitology. Vol. 24: 143–150. 2008.

- "The Medical Letter." Drugs for Parasitic Infections. 2005. www.medicalletter.org/parasitic_cdc.

- WHO/FAO. "Food-Borne Trematode Infections in Asia." Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2002.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Metagonimiasis Archived 2007-10-08 at the Wayback Machine