Jones–Liddell feud

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Jones–Liddell feud | |||

|---|---|---|---|

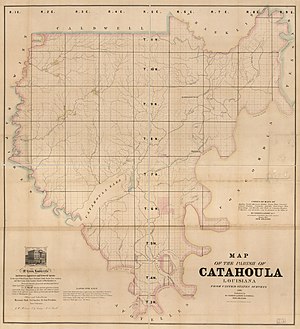

Catahoula Parish in 1860, Location of the Jones–Liddell Feud | |||

| Date | 1847–1870 | ||

| Location | 31°33′N 91°49′W / 31.55°N 91.82°W | ||

| Caused by | Rivalry plantations; revenge killings | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

Lt. Col. Charles Jones | |||

The Jones–Liddell feud (1847–1870) also known as the Liddell–Jones feud or the Black River War was a warring dispute between two prominent families from Catahoula Parish, Louisiana. It resulted in the death of at least six people, with other estimates suggesting as many as fourteen.

Background

Personal allegiances to one faction or another, as well as sensationalized press accounts during and after the series of events provide for a variance of details concerning the Jones-Liddell feud. It was born, however, from disagreements between two individuals: Gen. St. John Richardson Liddell and Lt. Col. Charles Jones. Each of these men were members of the Whig Party in the 1850s, and held significant wealth leading up to the Civil War.[1] Liddell was the second largest slave owner in Catahoula parish, with 115 slaves, while Jones owned 101 slaves. Each served as the patriarch of his respective family, with children who also would become participants in the feud. Both of these rivaling plantation owners arrived in Catahoula Parish at approximately the same time (1837–1840), and each would later serve in the Confederate Army. Following the war, however, Liddell remained a loyal Democrat and defender of the southern cause. Jones, however, became a Republican convert, at a time when the federal government installed Republican loyalists in government across the state.[2]

Liddell was the son of a wealthy plantation owner from Wilkinson County, Mississippi. After reaching the age of adulthood, he moved to Catahoula Parish on the Black River, and constructed a plantation which he named "Llanada" near Harrisonburg, Louisiana. Liddell had attended West Point, and was a personal friend of future Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Jones was born in Kentucky, married in Ohio, and eventually settled in Catahoula Parish and established a plantation named "Troy," also on the Black River, approximately five miles south of Liddell's plantation. Jones was second in command of the 17th Volunteer Louisiana Infantry, but was injured early in the war.[3]

Antebellum

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (October 2019) |

Origin

According to Liddell, the origin of the feud involved a neighboring family to both Liddell and Jones. Phillip and Eliza Nichols, who were personal friends of the Liddell family, owned a prominent piece of land that Jones greatly coveted. Liddell's accounts suggest that Jones had publicly maligned the character and virtue of Mrs. Nichols. Mrs. Eliza Nichols made a personal request for Liddell to accompany her in confronting Jones about his efforts to disparage her character. Liddell agreed and together they confronted Jones at his home. As Mrs. Nichols approached Jones, however, she pulled out a pistol and shot him in the face, an action that Liddell claimed he did not expect from her, nor have prior knowledge of.[4]

Jones was injured, but the gunshot did not kill him. According to Liddell, Jones solely placed the blame on Liddell rather than hold Mrs. Nichols as the responsible party for his injury. As Jones rested at home in recovery, rumors began to escalate that Jones was plotting a revenge attack on Liddell and his family. The tensions would continue to escalate, and each family found themselves consumed with fortifying their respective plantations, and stocking up on guns and ammunition. Residents in the community feverishly fueled these tensions, and unofficial factions began to form throughout the area.[5]

Tensions between the two feuding families found a temporary reprieve, when Jones and his wife left for Ohio for a period of four years. Liddell suggested that Jones continued to send threats to Liddell during this time, stating his intention to return and kill him. In 1852, Jones made his return to his plantation on the Black River, accompanied by hired assassins, including one notoriously known as such by the name of Richard Pryor according to Liddell.[5] Sam Smith, a nephew of Jones, added his name to the list of those publicly professing he would kill Liddell.[5]

Murders of Wiggins and Glenn

Another Jones sympathizer by the name of Samuel Glenn made public threats against Liddell and his family. Liddell was tipped off that Glenn and Pryor were in town and had plans for another attempt on his life. On June 26, 1852, Samuel Glenn and a neighbor of Liddell's by the name of Moses Wiggins were ambushed by the road near "Trinity." Liddell admitted to having killed them both, but claimed that he mistook Moses Wiggins for Pryor. Liddell was arrested for murder.[6] Liddell's friends and allies defended his actions due to the public threats that had been levied toward his life. Liddell hired well-established attorneys from Natchez, Louisiana. Despite two grand juries, Liddell was acquitted in 1854.[6]

The feud quieted down as a result of the American Civil War. Both Liddell and Jones each enlisted in support of the Confederate cause.

Reconstruction Era

Following the defeat of the Confederate States, both Liddell and Jones each returned home to try and salvage the once prosperous plantations. The economic fate of each man would be determined over the next five years largely by the political choices each made.[2] According to Liddell:

During these early years of reconstruction, a political divide was created that ultimately resulted in terror and lawlessness throughout the south. With post-war government being installed by federal forces, southern sympathizers and loyal Democrats found themselves on the outside looking in. Only days before President Lincoln's assassination, he installed William Pitt Kellogg as the federal collector of customs in New Orleans. This began a twenty-year reign by the northerner in what became known as the Kellogg Government. Natives of the state resisted violently and violence occurred throughout the state.[8]

Economic status

When Liddell returned to "Llanada" after the war, it was on the verge of financial ruins. No longer able to utilize slave labor, and with banks setup by northerners lending money at high interest rates, Liddell faced complete ruin, and would ultimately see his beloved Llanada forced into a sale at public auction, in order to cover Liddell's debts.

Jones on the other hand did not face the same economic fate. When Liddell's Llanada was placed up for auction, Jones began to negotiate with a third party to purchase the place. Upon discovering Jones' interest in acquiring his property, Liddell sent a warning to Jones, intimating bluntly that he could not stand for Jones to seize the property which held the graves of his dead family. Once again, tensions became heated between the two factions.

Assassination of Liddell

Both Liddell and Jones were frequent visitors to New Orleans, which could be reached by riverboat with moderate ease. In 1870, Liddell had boarded the steamer on the Black River heading to New Orleans. The captain knew that Jones had coincidentally also planned a trip to New Orleans and would be boarding the steamer. Sensing potential trouble ahead, he alerted Liddell of this news. Liddell had him send word to Jones that he should not board the steamer. Upon receiving this news, Jones gathered his sons and took off by horseback to a loading dock south of his own landing.[9]

When the steamer pulled in at that place, Liddell was seated having lunch. Jones and his sons boarded the steamer and drew their weapons on Liddell. Upon seeing their entry, the captain alerted Liddell that the men were coming to murder him. Liddell rose to draw his weapon in defense, but Jones and his sons fired, killing Liddell instantly.[9][10]

Jones' arrest and revenge

Upon hearing the news of Liddell's death, shock and horror enveloped the entire region. Jones and his sons were placed under arrest, but Sheriff Oliver Ballard, a Republican ally of Jones, allowed them to remain in custody at his personal home.[11]

Days after the murder of Liddell, his son Moses "Judge" Liddell was traveling on a steamer near the Sheriff's home where Jones and his sons had been placed under house arrest. While passing this place, Moses Liddell saw Jones walking down near the river, and raised his gun and took aim. He fired upon Jones, making no excuse for himself other than retribution for the murder of his father. Moses Liddell's shot, however, did not kill Jones.[11]

The local residents, who were largely Democrat-aligned and against the northern Reconstruction efforts, demanded retribution against Jones but suspected that none would come due to Jones' Republican political ties. A mob formed and stormed the place where Jones and his sons were being held. The mob ultimately killed Jones, as well as his son William. Others found at the place were spared. One son of Jones, Cuthbert Bullitt, slipped out of a second story window, and held on to the ledge, so as not to be found. His life was spared as a result.[11]

The deaths from the mob were the last in the feud. Liddell was buried at Llanada plantation. Jones and his son were both interred on the family cemetery at his Everly Plantation.[12]

Aftermath

The community of Jonesville, Louisiana, was established near Everly plantation, after Jones' widow helped establish it. The area had been known as Trinity, but Jonesville became her name of choice for the new town.[13]

Moses "Judge" Liddell moved his family from the area, taking residence in Richland Parish on the banks of Boeuf River. There he was elected to the Louisiana House of Representatives. He later moved to Monroe, and was appointed by Democratic President Grover Cleveland as a justice on the Supreme Court of territorial Montana.[14]

Cuthburt Jones, having narrowly survived the lynch mob, made a trip to Washington, where he met with President Grant and relayed the tragic events of the feud. Being loyal and sympathetic to Jones, Grant appointed him as a consul to Tripoli in 1876. Louisiana Democrats later called upon President Grover Cleveland to rescind Cuthbert's consul appointment in 1885, alleging he was a "known murderer."[15] He would go on, however, to have a distinguished career as a foreign diplomat, including time as the consul to Peru. Cuthbert Bullit Jones died in South America in 1905.[16][17]

Francois Jones, the youngest son of Jones, also left Louisiana as a result of the feud. He became a prominent citizen in Washington, D.C, but drowned while attempting to cross a turbulent river near there in 1900.[18]

In 2008, descendants of the family and residents of the surrounding areas gathered for a re-enactment of the events that took place in the Jones–Liddell feud.[19]

See also

- List of feuds in the United States

- Conclusion of the American Civil War

- Reconstruction Era

- Colfax massacre

Further reading

- Crawford, W. M. The Jones-Liddell Feud, Catahoula Parish, 1852–1870. OCLC 36024921.

- King, Major Michael R. (2014-08-15). Brigadier General St. John R. Liddell's Division At Chickamauga: A Study Of A Division's Performance In Battle (Illustrated ed.). San Francisco: Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 9781782893967.

References

- ^ ROBERTSON, HENRY O (2012). "Who Were the Whigs of Catahoula Parish, 1840?". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 53 (3): 292–317. JSTOR 23266744.

- ^ a b Liddell & Hughes 1997, p. 203.

- ^ "United States Census, 1860". FamilySearch.com. National Archives and Records Administration, n.d. p. Louisiana > Catahoula > Harrisonburg > image 2 of 2. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Liddell & Hughes 1997, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Liddell & Hughes 1997, p. 24.

- ^ a b Liddell & Hughes 1997, p. 25.

- ^ Zenneck, A. (1871). "Murder of Louisiana sacrificed on the altar of radicalism". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ Liddell & Hughes 1997, p. 202.

- ^ a b "19 Feb 1870, Page 2 - The Ouachita Telegraph at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ^ Liddell & Hughes 1997, p. 205.

- ^ a b c "12 Jul 1885, 1 - The San Francisco Examiner at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ^ "25 Feb 1973, Page 43 - The Town Talk at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ^ Liddell & Hughes 1997, p. 21.

- ^ "24 Dec 1887, Page 3 - The Ouachita Telegraph at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ^ "1 Jun 1885, Page 1 - The New York Times at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ^ "15 Aug 1876, 1 - New Orleans Republican at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ^ "Cuthbert Jones Dies in Peru". The Washington Times. September 10, 1905. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ "1 Mar 1910, Page 6 - The Washington Post at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ^ Hogan, Vershal (October 31, 2009). "Longtime Catahoula parish feud to reignite next weekend". The Natchez Democrat. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

Bibliography

Liddell, St. John Richardson; Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs (1997). Liddell's record. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0807122181. OCLC 37001517.

External links

- The Last of Louisiana's Aristocratic Feudists Upsets Family Traditions By Dying A Natural Death on Newspapers.com (1905)[1]

- Hatfields and McCoys Part II: The Black River War - Tim Kent's Civil War tales

- ^ "1 Oct 1905, Page 36 - The Washington Times at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- Articles with short description

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Articles needing additional references from September 2018

- All articles needing additional references

- Wikipedia neutral point of view disputes from October 2019

- All Wikipedia neutral point of view disputes

- Articles with multiple maintenance issues

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles needing additional references from October 2019

- Louisiana folklore

- Feuds in the United States

- Deaths by firearm in Louisiana

- Catahoula Parish, Louisiana