Blueberry muffin baby

| Blueberry muffin baby | |

|---|---|

| |

| A newborn baby with typical lesions of a blueberry muffin baby. | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics, dermatology |

| Symptoms | Reddish-blue purpura localized mainly to the face, neck, and trunk[1] |

| Causes | Congenital rubella, congenital CMV, other TORCH infections, blood disorders, and malignancies[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests for complete blood count, TORCH infections, haemoglobin, viral cultures and Coombs test, skin biopsy[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Hemangiopericytoma, blue rubber bleb nevus, hemangioma, glomangioma[1] |

| Prevention | MMR vaccine covers for congenital rubella |

| Frequency | Uncommon[2] |

Blueberry muffin baby, also known as extramedullary hematopoiesis, describes a newborn baby with multiple purplish small bumps, associated with several non-cancerous and cancerous conditions in which extra blood is produced in the skin.[1] The bumps range from 1-7mm, do not blanche and have a tendency to occur on the head, neck and trunk.[1] They often fade by 3 to 6 weeks after birth, leaving brownish marks.[3] When due to a cancer, the bumps tend to be fewer, firmer and larger.[2]

It can occur following infection of an unborn baby with rubella, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, or coxsackie virus.[4] Other viral causes include parvovirus B19 and herpes simplex.[1] Non-infectious causes include haemolytic disease of the newborn, hereditary spherocytosis, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and recombinant erythropoietin administration.[1] Some types of cancers can cause it such as rhabdomyosarcoma, extrosseal Ewing sarcoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, congenital leukaemia and neuroblastoma.[1] During normal development of an unborn baby, blood production can occur in the skin until the fifth month of pregnancy.[3] Blueberry muffin lesions in the newborn indicate the prolongation of skin blood production after birth.[3]

Diagnosis involves a combination of appearance and laboratory studies, including blood tests for complete blood count, TORCH infections, haemoglobin, viral cultures and Coombs test.[1] A skin biopsy may be useful.[1] Conditions that may appear similar include hemangiopericytoma, blue rubber bleb nevus, hemangioma and glomangioma.[1]

Prognosis is variable based upon the cause of the characteristic rash. Treatment may include supportive care, anti-viral medication, transfusion, or chemotherapy depending on the underlying cause.

It is not common.[2] The term was coined in the 1960s to describe the skin changes in babies with congenital rubella.[2] Since then, it has been realised that blueberry muffin marks occur in several conditions.[2]

Signs and symptoms

The bumps and marks range from 1-7mm, do not blanche and have a tendency to occur on the head, neck and trunk.[1] The baby may be anaemic, appear yellow, have a large large liver and spleen and have poor growth.[5]

-

purplish bumps in skin due to neonatal Langerhans cell histiocytosis

-

marks and bumps head, neck and chest

Causes

Blueberry muffin baby can occur following infection of an unborn baby with rubella, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, or coxsackie virus.[4][6] Other viral causes include parvovirus B19 and herpes simplex.[1] Non-infectious causes include haemolytic disease of the newborn, hereditary spherocytosis, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and recombinant erythropoietin administration.[1] Some types of cancers can cause it such as rhabdomyosarcoma, extrosseal Ewing sarcoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, congenital leukaemia and neuroblastoma.[1] During normal development of an unborn baby, blood production can occur in the skin until the fifth month of pregnancy.[3] Blueberry muffin lesions in the newborn indicate the prolongation of skin blood production after birth.[3][7]

Listed below are a few known conditions[3][8] that can cause a blueberry muffin baby.

Infectious

- Toxoplasmosis: TORCH infection due to Toxoplasma gondii parasite. Condition is commonly associated with undercooked meat or contact with cat feces. Symptoms of this disease include seizures, hydrocephalus, and chorioretinitis.

- Cytomegalovirus: viral TORCH infection associated with sensorineural hearing loss, hepatomegaly, and jaundice.

- Rubella: viral TORCH infection associated with post-auricular and occipital lymphadenopathy in addition to a maculopapular rash that starts on the face and spreads to the trunk.

- Herpes virus: viral TORCH infection associated with painful vesicular lesions and meningitis.

- Syphilis: bacterial TORCH infection due to Treponema pallidum. Congenital syphilis can present with saber shins, saddle-shaped nose, Hutchinson's teeth, and deafness.

- Epstein Barr virus: viral infection that causes infectious monocleosis. Condition is associated with lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and various lymphomas

Hematologic

- Hereditary spherocytosis: autosomal dominant disease that results in formation of aberrant erythrocyte membrane protein. This condition results in structural change of red blood cells (RBCs), shearing of RBCs, and anemia.

- Hemolytic disease of the newborn (ABO or Rh incompatibility): Condition is due to maternal and fetal red blood cell mismatch. Maternal antibodies destroy fetal RBCs which results in anemia.

Neoplastic

- Neuroblastoma: pediatric cancer due to malignancy in neuroblast cells. Tumor is usually localized to the adrenal glands.

- Congenital leukemia: pediatric cancer due to malignancy of white blood cells.

- Congenital rhabdomyosarcoma: pediatric cancer due to malignancy of muscle cells.

Systemic

- Langerhans cell histocytosis (LCH): Condition due to excess build-up of Langerhans cells.

- Lupus: autoimmune disease

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical presentation, physical exam, and laboratory studies. When this characteristic rash is found in a neonate, laboratory workup is prompted.

Initial workup usually includes a complete blood count (CBC) with differential to evaluate for underlying blood disorders.[7] Laboratory confirmation of the cause of the blueberry muffin rash depends on the underlying illness.

For example, serology positive for rubella specific antibodies, viral culture with isolated rubella, or isolation of rubella virus RNA through polymerase chain reaction can all confirm that congenital rubella infection is the underlying cause of the blueberry muffin rash.[9] Other manifestations of congenital rubella disease can also appear in conjunction with the characteristic rash. These include congenital glaucoma, jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, microcephaly, cataracts, or sensorineural hearing loss. The presence of these features can further bolster the diagnosis of congenital rubella as the cause of the blueberry muffin baby.[9] Laboratory studies for congential rubella infection should be done prior to 1 year of age as diagnosis becomes more challenging afterwards.[10]

In the case of infection with cytomegalovirus (CMV), patients can present with associated symptoms such as deafness and chorioretinitis. On lab studies, there may be a high anti-cytomegalovirus antibody titer, positive CMV urine culture, and thrombocytopenia.[3]

If the cause is due to hemolytic disease of the newborn or hereditary spherocytosis, the neonate will have a positive Coomb's test and unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.[3]

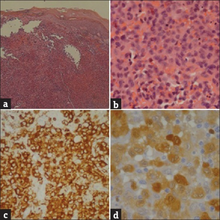

Malignancies such as neuroblastoma and acute myeloid leukemia are all rare but possible causes of a blueberry muffin baby. Most of the time, these conditions are diagnosed using immunohistochemistry and biopsy.[3]

Treatment

Treatment is based on underlying cause. If significant anemia is present, blood transfusion may be indicated.[8] In the case of congenital rubella infection, there is no known cure. Therefore, the focus of treatment is disease prevention. The MMR vaccine is highly efficacious in preventing congenital rubella and is given routinely as a part of the pediatric vaccine schedule.[11] For neonates with congenital CMV infection, antiviral medication is given. Most commonly, valganciclovir or ganciclovir are used as first-line antiviral therapy for congenital CMV.[12] If the cause is a malignancy, the patient should receive cancer treatment such as chemotherapy.[7]

Outcome

Outcome is based on underlying cause. Usually the lesions should resolve within three to six weeks post-delivery.[3] There has been a documented case of the rash completely resolving following a blood transfusion to treat severe anemia in a neonate.[8] The rash is usually transient and will resolve once the underlying cause is treated.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2020). "35.Cutaneous vascular diseases". Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. p. 831. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6. Archived from the original on 2023-04-29. Retrieved 2023-04-29.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Manning, Jamie Rosen; Lee, Diana H. (1 January 2019). "Uncommon Neonatal Skin Lesions". Pediatric Annals. 48 (1): e30–e35. doi:10.3928/19382359-20181212-02. ISSN 1938-2359. PMID 30653640. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Mehta, Vandana; Balachandran, C.; Lonikar, Vrushali (28 February 2008). "Blueberry muffin baby: a pictoral differential diagnosis". Dermatology Online Journal. 14 (2): 8. doi:10.5070/D353q852nc. ISSN 1087-2108. PMID 18700111. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "12. Disorders of elastic tissue". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 763. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ "Blueberry muffin syndrome | DermNet NZ". dermnetnz.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ↑ Domachowske, Joseph; Suryadevara, Manika (2020). "26. Congenital and perinatal infections". Clinical Infectious Diseases Study Guide: A Problem-Based Approach. Switzerland: Springer. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-3-030-50872-2. Archived from the original on 2023-08-20. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Debord, Camille; Grain, Audrey; Theisen, Olivier; Boutault, Robin; Rialland, Fanny; Eveillard, Marion (February 2018). "A blueberry muffin rash at birth". British Journal of Haematology. 182 (2): 168. doi:10.1111/bjh.15135. ISSN 1365-2141. PMID 29468630. Archived from the original on 2022-03-26. Retrieved 2021-11-15.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Bagna, R.; Bertino, E.; Rovelli, I.; Peila, C.; Giuliani, F.; Occhi, L.; Mensa, M.; Mazzone, R.; Saracco, P.; Fabris, C. (June 2010). "Benign transient blueberry muffin baby". Minerva Pediatrica. 62 (3): 323–327. ISSN 0026-4946. PMID 20467386. Archived from the original on 2021-11-09. Retrieved 2021-11-15.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Rubella, Congenital Syndrome (CRS) 2007 Case Definition | CDC". Archived from the original on 2021-12-10. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ↑ Kimberlin, David (2018). Red Book 2018-2021 Report of Committee on Infectious Diseases. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics. p. 705. ISSN 1080-0131.

- ↑ Lambert, Nathaniel; Strebel, Peter; Orenstein, Walter; Icenogle, Joseph; Poland, Gregory A. (2015-06-06). "Rubella". Lancet. 385 (9984): 2297–2307. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60539-0. ISSN 1474-547X. PMC 4514442. PMID 25576992. Archived from the original on 2021-11-17. Retrieved 2021-11-15.

- ↑ Nassetta, Lauren; Kimberlin, David; Whitley, Richard (May 2009). "Treatment of congenital cytomegalovirus infection: implications for future therapeutic strategies". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 63 (5): 862–867. doi:10.1093/jac/dkp083. ISSN 1460-2091. PMC 2667137. PMID 19287011. Archived from the original on 2021-11-08. Retrieved 2021-11-15.