Black hairy tongue

| Black hairy tongue | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Lingua villosa nigra[1][2] melanoglossia,[3] hairy tongue[4] | |

| |

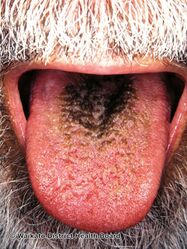

| A picture of black hairy tongue | |

| Specialty | ENT surgery |

| Symptoms | Discoloration and enlarged pumps on the outer surface of the tongue[5] |

| Complications | Bad breath, altered taste, burning[5] |

| Usual onset | > 40 years old[4] |

| Risk factors | Smoking, alcohol, dry mouth, poor oral hygiene, coffee, certain medications[5][4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on appearance[5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Hairy leukoplakia, acanthosis nigricans[5] |

| Treatment | Good mouth care, brushing with toothbrush, reassurance[5] |

| Medication | Applying 3% hydrogen peroxide[4] |

| Prognosis | Good[5] |

| Frequency | 1% to 11%[5] |

Black hairy tongue (BHT) is a condition in which small bumps on the tongue elongate with typically a black or brown discoloration.[6] Other colors such as green or blue may occur.[5] Other than the appearance; there are generally no further symptoms.[5] Occasionally bad breath, altered taste, or burning may occur.[5]

Risk factors include smoking, alcohol, dry mouth, poor oral hygiene, coffee, poor health, and certain medications.[4][5] Medications associated with the condition include erythromycin, doxycycline, bismuth, and olanzapine.[4] Diagnosis is generally made based on the appearance, though tissue biopsy may be carried out in unclear cases.[5][4]

Treatment involves addressing the underlying cause together with good oral care.[5] Gently scrubbing the tongue with a toothbrush may help, as may the use of 3% hydrogen peroxide on the area.[4] Outcomes are good.[5]

Black hairy tongue effects between 1% and 11% of people.[5] It occurs most commonly in those over the age of 40.[4] Males are more commonly affected than females.[5] The condition was first described in 1557 by Amatus Lusitanus.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Hairy tongue largely occurs in the central part of the dorsal tongue, just anterior (in front) of the circumvallate papillae, although sometimes the entire dorsal surface may be involved.[7] Discoloration usually accompanies hairy tongue, and may be yellow, brown or black.[7] Apart from the appearance, the condition is typically asymptomatic, but sometimes people may experience a gagging sensation or a bad taste.[7] There may also be associated oral malodor (intra-oral halitosis).[7]

The term "melanoglossia' is also used to refer to there being black discolorations on the tongue without "hairs", which are also harmless and unrelated to black hairy tongue.[8]

-

Black hairy tongue

-

Black hairy tongue

-

Black hairy tongue

-

Black hairy tongue

Causes

The cause is uncertain,[7] but it is thought to be caused by accumulation of epithelial squames and proliferation of chromogenic (i.e., color-producing) microorganisms.[9] There may be an increase in keratin production or a decrease in normal desquamation (shedding of surface epithelial cells).[7] Many people with BHT are heavy smokers.[7] Other possible associated factors are poor oral hygiene,[7] general debilitation,[7] hyposalivation (i.e., decreased salivary flow rate),[9] radiotherapy,[7] overgrowth of fungal or bacterial organisms,[7] and a soft diet.[9] Occasionally, BHT may be caused by the use of antimicrobial medications (e.g., tetracyclines),[9] or oxidizing mouthwashes or antacids.[7] A soft diet may be involved as normally food has an abrasive action on the tongue, which keeps the filiform papillae short. Pellagra, a condition caused by niacin (vitamin B3) deficiency, may cause a thick greyish fur to develop on the dorsal tongue, along with other oral signs.[10]

Transient surface discoloration of the tongue and other soft tissues in the mouth can occur in the absence of hairy tongue. Causes include smoking (or betel chewing),[9] some foods and beverages (e.g., coffee, tea or liquorice),[9] and certain medications (e.g., chlorhexidine,[9] iron salts,[9] or bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol)).[11]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually made on the clinical appearance without the need for a tissue biopsy.[7] However, when biopsies have been taken, the histologic appearance is one of marked elongation and hyperparakeratosis of the filiform papillae and numerous bacteria growing on the epithelial surface.[7]

Hairy tongue may be confused with hairy leukoplakia, however the latter usually occurs on the sides of the tongue and is associated with an opportunistic infection with Epstein–Barr virus on a background immunocompromise (almost always human immunodeficiency virus infection but rarely other conditions which suppress the immune system).[7]

Classification

Hairy tongue (lingua villosa) refers to a marked accumulation of keratin on the filiform papillae on the dorsal surface of the tongue, giving a hair-like appearance.[7] Black tongue (lingua nigra) refers to a black discoloration of the tongue, which may or may not be associated with hairy tongue. However, the elongated papillae of hairy tongue usually develop discoloration due to growth of pigment producing bacteria and staining from food.[7] Hence the term black hairy tongue, although hairy tongue may also be discolored yellow or brown. Transient, surface discoloration that is not associated with hairy tongue can be brushed off.[9] Drug-induced black hairy tongue specifically refers to BHT that develops because of medication.[12]

Treatment

Treatment is by reassurance, as the condition is benign, and then by correction of any predisposing factors.[7] This may be cessation of smoking or cessation/substitution of implicated medications or mouthwashes. Generally direct measures to return the tongue to its normal appearance involve improving oral hygiene, especially scraping or brushing the tongue before sleep.[9] This promotes desquamation of the hyperparakeratotic papillae.[7] Keratolytic agents (chemicals to remove keratin) such as podophyllin are successful, but carry safety concerns.[7] Other reported successful measures include sodium bicarbonate mouthrinses, eating pineapple, sucking on a peach stone and chewing gum.[9]

Prognosis

BHT is a benign condition,[7][13][14] but people who are affected may be distressed at the appearance and possible halitosis, and therefore treatment is indicated.

Epidemiology

The prevalence is variable depending on the population studied.[12] Hairy tongue generally occurs in about 0.5% of adults.[7]

References

- ↑ Rajendran, R.; Sivapathasundharam, B., eds. (2009). "Developmental Disturbances of Oral and Paraoral Structures". Shafer's Textbook Of Oral Pathology (6th ed.). Elsevier India. p. 31. ISBN 978-8131215708. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- ↑ Waggoner, W. C.; Volpe, A. R. (January 1967). "Lingua Villosa Nigra--A Review of Black Hairy Tongue". Journal of Oral Medicine. 22 (1): 18–21. PMID 5340144.

- ↑ "Melanoglossia". The Lancet. 197 (5096): 922. 30 April 1921. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)55600-1.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Wright, Beth (2014). "Hairy tongue". dermnetnz.org. DermNet NZ. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 Gurvits, GE; Tan, A (21 August 2014). "Black hairy tongue syndrome". World journal of gastroenterology. 20 (31): 10845–50. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10845. PMID 25152586.

- ↑ James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2020). "34. Disorders of the mucous membranes". Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. p. 799. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6. Archived from the original on 2023-04-11. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 Neville, Brad W.; Damm, Douglas D.; Allen, Carl M.; Bouquot, Jerry E. (2002). Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology (Second ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0721690032.

- ↑ Maynard, F. P. (October 1897). "A Note on Melanoglossia". The Indian Medical Gazette. 32 (10): 364–365. PMC 5148483. PMID 29002878.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 Scully, Crispian (2008). Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine: The Basis of Diagnosis and Treatment (Second ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 349. ISBN 978-0443068188.

- ↑ Cawson, Roderick A.; Odell, Edward W. (2002). Cawson's Essentials of Oral Pathology and Oral Medicine (Seventh ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 351. ISBN 978-0443071058.

- ↑ Cohen, Philip R. (December 2009). "Black tongue secondary to bismuth subsalicylate: case report and review of exogenous causes of macular lingual pigmentation". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 8 (12): 1132–5. PMID 20027942.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Thompson, Dennis F.; Kessler, Tiffany L. (June 2010). "Drug-induced black hairy tongue". Pharmacotherapy. 30 (6): 585–93. doi:10.1592/phco.30.6.585. PMID 20500047.

- ↑ Gurvits, Grigoriy E.; Tan, Amy (21 August 2014). "Black hairy tongue syndrome". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (31): 10845–50. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10845. PMC 4138463. PMID 25152586.

- ↑ Yuca, Köksal; Calka, O.; Kiroglu, A. F.; Akdeniz, N.; Cankaya, H. (2004). "Hairy tongue: a case report". Acta Oto-rhino-laryngologica Belgica. 58 (4): 161–3. ISSN 0001-6497. PMID 15679200.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |